Jacari White left the YMCA and slid into his dad’s 2017 Nissan Altima before they drove in the direction of the Coca Cola warehouse, where White’s father was set to work the overnight shift. By the time White’s father entered the building each night, his eighth-grade son was in the backseat of the Altima winding down for bed. It was a daily routine.

While White’s father was working overnight as a machine operator so that he could take his son to school in the morning, White was asleep. As a result of his parents splitting, his grandfather passing away, the company his father worked for closing down and the ripple effects of the past, staying in the car was the only option for White. The reality would last until White’s sophomore year of high school.

“It was hard having to go through that while trying to navigate your high school life,” White told Basket Under Review. “I felt I was very separated from everyone else because I couldn’t really do much with them outside of school. We didn’t have much money.”

White’s routine prior to his arrival in his father’s car didn’t offer much reprieve from the severity of his reality that his sleeping situation indicated. The family didn’t have much, but White’s father did have a YMCA membership that allowed his son to develop some form of consistency.

Every morning, White would head to the YMCA to shower before school began. He would go to school, then return to the YMCA in the afternoon to do his homework and work out until his dad picked him up at night. White says he was on a first-name basis with “everybody” in the building, that he had to “do everything there” and that his constant presence “felt embarrassing at first.”

White wasn’t difficult to locate back then and wasn’t hard to pick out of a crowd, either. The now-Virginia guard–who has become a go-to guy for the Wahoos in Ryan Odom’s first year at the helm–says he had to wear “basically the same clothes every day." He pulled clothes out from a bag in the backseat of the Altima each day–alongside a “beat up” pair of Nike Huaraches and a pair of basketball shoes that were given to him.

“I definitely had people support me, but I also had people that made fun of me,” White said. “It was rough. I really struggled with my confidence.”

White’s high school coach Rob Gordon says that White was always well liked, but that he was never “outspoken” or a “popular with the crowd kind of guy.” The battle for confidence was almost to be expected through White’s life full of challenges–which included his hair falling out at seven years old due to Alopecia–but he knew that his circumstances didn’t have to define him.

If he didn’t learn it as a result of circumstance, White’s father, Tim, made sure to pound into his head that “you have to work hard for what you want in life and nothing is given to you.” The reality was sobering, but it was sure to eliminate pouting and entitlement from the equation. White received the message by eventually offering to help with finances by picking up a job of his own before his father told him just to focus on basketball and succeeding academically. The idea that White’s father would give his “lung, his kidney, his heart, his whatever” for his kids was one that Sharon Warner–a family friend of the White’s believed in.

Tim made every effort to give his son–and his daughter, who moved in with a cousin–a chance to live like a normal kid despite his lack of means. But, White inevitably had to grow up quickly. Part of the experience White learned was essential was getting up and putting on a brave face regardless of circumstance.

“Unless you knew the intimate details of his life, you wouldn’t know,” Gordon said. “He always had a positive outlook and a positive frame of mind. Nobody would know.”

Perhaps the nature of White’s outlook had some unwarranted positivity behind it. Perhaps it was the only way to stay sane as he lived in his reality. At times White’s mentality made it look easy.

It wasn’t, though. Nothing about it was.

“It was tough back then,” White’s father said. “Had to make money to pay the bills. I didn’t want to rely on anybody. You gotta do what you gotta do.”

It wasn’t part of Warner’s plan, but she couldn’t resist allowing White and his sister to bring their pet dog, Tan–who she describes as the “love of their lives”--to her house. As for the pair of siblings, Warner says it was the “easiest thing ever” to allow them to stay on the second floor of her home throughout his sophomore year of high school.

Warner’s son, Dennis, and White were teammates at Olympia High, Gotha Middle School and were already best friends. Warner says that White has “always” been a part of her family “in one way or another” and that he’s a “yes ma’am kid.” As a result, he and his sister were allowed to share a room in Warner’s house for “a good couple months” until their father was able to improve their situation.

“He has always been this really special kid, one of the kindest hearts. He has a heart of gold,” Warner told Basket Under Review. “Between him and his sister, I fell in love with them that way.”

Warner says that to this day she still hasn’t heard White cuss–although she jokes that she doesn’t know what happens on the basketball court. She says the only pair of siblings she’s ever seen not argue are White and his sister and that the only time she’s ever been upset with him is when he left his shoes at her house before a game, although she “didn’t yell at him too bad for that one.”

For as much potential as Warner knew White and his sister–who is graduating high school this year–had, she also knows that “kids who grew up like Jacari and his sister” don’t often have life outcomes “as great as Jacari or his sister.” She knew that she could help and wanted to make sure that they were able to stay in the school system where they were “flourishing.”

Warner was careful not to “pull anything” away from White and his sister, provided them shelter, treated them as part of the family by calling them down for dinner–where Warner believes White’s favorite dish of hers is mac and cheese–every day and taught White how to cook before he left for college. When White came home from North Dakota State for Christmas break, he brought a teammate who didn’t have any family around back to Warner’s house. She says she still has the picture of the pair of former teammates sitting at her dinner table.

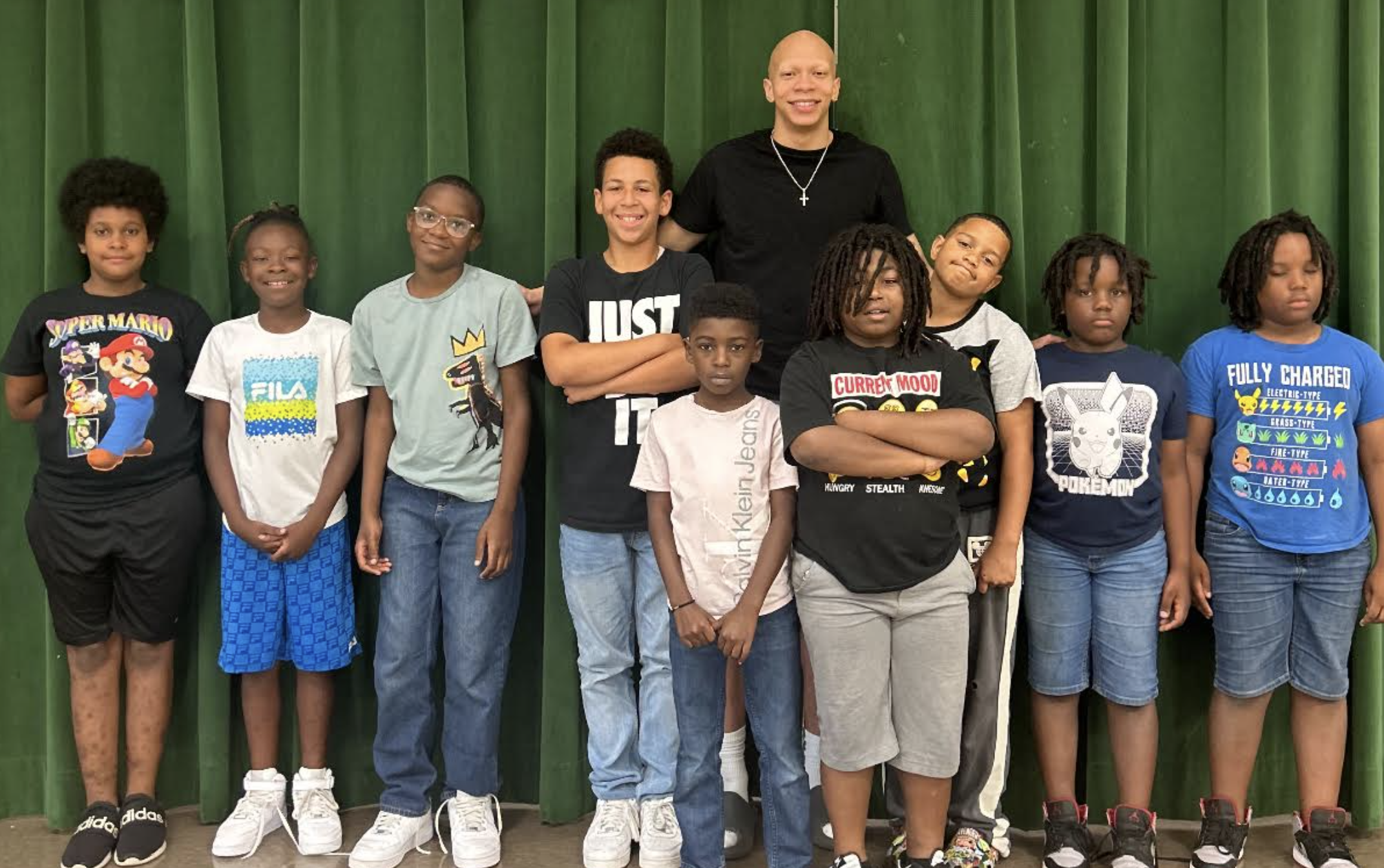

Alongside the photo in Warner’s archives are photos of White dressed up as a toy soldier at one of her events as well as pictures of he and his sister volunteering alongside her at Eccleston Elementary School. When White came back from college, he spoke to the kids about dealing with Alopecia and how “you may or may not look like everyone else, but there’s value in you.” Warner–who is the founder and executive director of a non-profit called Youth Families and Communities United INC.--says that two kids that she often sees often ask how “Mister. Jacari” is.

Whether White was living with Warner or not, she was involved. She was also his loudest supporter at each high school game and would likely fill the same role if she were to travel to Charlottesville to see him play at Virginia. Perhaps the family friend label isn’t strong enough to describe Warner’s role.

“Sharon, she was like the other mother that helped out with everything,” White’s father said. “She really helped raise them in certain things like school and different aspects. She definitely stepped up when we needed her.”

In the power rankings of heroes in White’s life, Tim White and Sharon Warner have to rank near the top. Each of them–particularly Warner–had to go far out of their own ways to get White to where he is as a double-figure scorer at Virginia that’s set to graduate with another prestigious degree.

The success has validated Warner’s investment, yet she doesn’t need it to believe that she made the right decision when White was a high schooler. Perhaps more than his achievements, Warner admires White’s care for his sister daily and the way he’s intentionally worked to become an example for her. The idea of his act of service and care is a microcosm of why she’s gravitated toward him.

“If I ever had to do it over again for Jacari and his sister,” Warner said, “I would do it over and over and over again. That’s just how good those kids were.”

The world around White was constantly changing and the weight of it was often heavy, but he knew all along that he had a safe haven. For an extended period of time each day–when White stepped onto the basketball court at the YMCA or at Olympia High–none of his circumstances mattered, all that did was the game that White was passionate about.

When White wasn’t playing–which wasn’t often–he was up running early in the morning trying to get his conditioning. When the opportunity to move schools to make some of the family’s circumstances better presented itself, White’s father was intentional about keeping him within the same basketball program. Each of them believed that there was something here beyond passion.

“It was something I felt like I had to stay with, it was all I had,” White said. “Whenever I stepped on the court, whoever was in front of me was not better than I was. I felt like I was the best on the court. Having that mindset, I feel like that really helped me because I wanted to prove that every time I played.”

White is the consummate college basketball underdog that could only succeed as a result of immense self belief. His circumstances off the floor were too difficult for him to make it any other way. On the floor, White was an underdog as a slow-to-grow, 5-foot-9 high school sophomore.

As soon as White was starting to prove that he could do what he believed he could throughout that sophomore season, his kneecap popped out of place during an early-season practice. The doctor popped the kneecap back into place and told White to sit out for a week and that once the week was up, he’d be cleared for action. Less than two weeks later, the knee dislocated again.

Those around White–including Gordon–knew after the second dislocation that he needed to seek further examination, but they knew that they’d have to go “backdoor” into a surgeon because White’s family “had no money, at all.” Gordon eventually worked a connection to find a professional athlete surgeon who was “more than happy” to see White at a minimal cost.

The surgeon performed an X-Ray and MRI on White’s knee, which led him to the jarring conclusion that White was dealing with an ACL injury. Upon further inspection, the surgeon concluded that he couldn’t do the surgery due to White’s growth plates being “wide open.”

That meant White was on the shelf. He would be from that moment–six games into his sophomore season–until the end of his junior season.

Once White’s junior season was over, his surgery was “finally” performed as the truth regarding his situation finally emerged. This was never an ACL problem. It was a meniscus problem. Instead of the 10-to-12 month rehab that appeared to be needed all along, White only needed six weeks to recover.

The good news for White; he could return in time to play the summer prior to his senior season. The bitter news; if his injury had been properly identified in the first place then he could’ve returned during the final weeks of his sophomore season and avoided missing any time as a high school junior. White had two choices as to how to view his situation; he could sulk about the bad news, or he could take the good news and run with it. He decisively chose one option over the other.

“He never had a bad attitude about it,” Gordon told Basket Under Review. “I was there on the morning of the surgery and he was just as happy as he could be that he would get to play again.”

“Jacari have anything yet?” a local high school basketball writer asked Gordon in regard to White’s offers.

“No,” Gordon replied.

“Hey,” the writer said, “I want to introduce you to this coach.”

The coach that Gordon introduced himself to shortly after the interaction had made the trip from State College of Florida to watch White and eventually became the only coach to recruit the senior guard. White was on a roster with one-time Charleston Southern and now-Texas Tech guard Tyeree Bryan as well as Cincinnati guard Jizzle James, yet the attention he received from college coaches was scarce at best. He was a zero-star recruit.

By the end of White’s senior season, State College of Florida was the only school to offer him a chance to play college basketball. Junior college it was for White.

White’s first college season appeared to prove that he was wrongly overlooked throughout his high school career and that his trajectory had shifted upwards. White averaged 13.5 points, 3.3 rebounds and 2.1 assists per game while shooting 39% from 3-point range and 92% from the free throw line as a freshman while playing his way into a First-Team All-Conference slot.

“I don't wanna sound cocky, but I was confident in my ability and I always felt like I should be playing at a higher level,” White said. “I never got the attention and I’ve just flown under the radar so it was just rough, but I always had the mindset that I was where I was supposed to be at and that I’ve got to work like I'm already there.”

White finally got his opportunity to be a factor at the level in which he felt he belonged as North Dakota State took a chance on him out of junior college. The sophomore guard proved North Dakota State head coach David Richman right as he became a rotational piece in his first Division-I season, became a double-digit scorer and an All-Summit League defender as a junior.

The breakout season appeared to come in White’s senior season as he went for 17.1 points and 4.3 rebounds per game while shooting 45.2% from the floor as well as 39.8% from 3-point range. The campaign wasn’t enough for White to receive All-Summit First-Team honors–he was instead subjected to the second team–but it was enough to make him a commodity in the transfer portal once he put his name in.

Being a flashy prospect was a different posture

“He’s an underdog because of everything we’ve been through,” White’s dad told Basket Under Review. “He’s been through different challenges in his life…He had to prove himself everywhere he went.”

White caught it, squared it up and let it rip from the left wing of the Charlotte Hornets’ Spectrum Center in an effort to make history. Earlier in the game, the Virginia guard had made his 11th-consecutive 3-pointer to tie Virginia legend Kyle Guy for most consecutive shots made from beyond the arc. By the end of White’s shot from the left wing, Guy could say he had a national title and was one of the all time greats in Virginia’s program. He couldn’t say that he had a program record.

The shot White had just let off didn’t touch the rim and was the finishing touch on a 25-point performance in which the Virginia guard shot 7-for-7 from beyond the arc. Perhaps more importantly, White sealed a program record with a 12th-consecutive made shot from 3-point range in just his ninth game as a member of it.

True to character, White– who averages 10.5 points a night--hasn’t taken long to prove himself in his first power-five opportunity. The North Dakota State transfer is 38th in the country in 3-point percentage, 59th in offensive rating, and would be tied for 14th in the country in effective field goal percentage and true shooting percentage if he was a qualified shooter.

“It’s a pleasure to coach Jacari,” Odom said. “When he gets in a zone like that, as his coach it’s like ‘stay out there,’ how long can we leave him out there before he gets tired.”

White has been described by a Virginia media member as a player that “is going to play the most electric 18 minutes per game you've ever seen” and has captivated the Virginia fanbase enough for them to form a fan section called the “Jacarmy.”

The group of Virginia students stands behind the away bench at John Paul Jones Arena in green t-shirts–made with the help of Chat GPT–with a portrait of White wearing an army uniform. White has acknowledged the Jacarmy consistently throughout the season after made shots.

Gordon says White’s fan club is “funny” to see because he was never “that outspoken” as a high schooler, but that he texted the Virginia guard and told him that he had to have one of the shirts. The fan section was started by a group of friends that had connected through various Christian organizations on Virginia’s campus and that they ran the idea by White prior to the season before it took shape.

Nowadays, the group of fans refers to themselves as soldiers in the Jacarmy and refer to White as their “general” while saluting him as he subs out. Their presence has become a piece of crucial lore in White’s nearly impossible-to-predict rise.

While the Jacarmy watches from the stands, White has his own army back home watching his every move and promoting the idea that his meteoric rise promotes the idea that anything is possible with the proper mindset.

If there’s anyone to promote that ideal, it’s White. Now that he’s here, he’s giving back to his father and sister while being a poster child for the positives of the Name, Image and Likeness era in college sports. How’d he get here? White’s father and Gordon would say it was a result of his son’s work and those who surrounded him. Warner has a simpler explanation.

“Something eventually will happen for good people, and he’s a good person,” she said, “And he’s always been a good person.”

White is proof of concept for those that struggle financially, don’t receive the recognition they feel they deserve or those who feel as if their current reality is insurmountable. “He’s an example of what can happen if you just work,” Gordon says.

Gordon says that his former guard is a “prime example of what it really takes” and what perseverance as well as the persistence it takes to make the climb that he has. The reality isn’t lost on White, nor will it ever be.

He hopes that his story isn’t the last like this. He knows it doesn’t have to be.

“Just keep working hard,” White said to those who are in difficult circumstances and want to be like him. “Somebody’s gonna see the hard work. People want to get behind you and support you. Even when it seems rough and nothing is going on, somebody is gonna see it. That work is always going to show.”