If a head coach is going to sport the suit-without-a-tie look along the sidelines of JPJ Arena — walking in the sartorial shadows of Tony Bennett — the team had better perform at a high level. So far, Ryan Odom is delivering. Virginia has already notched three wins over Top 70 programs, including double-digit victories away from Charlottesville against Texas and Dayton, and its offense ranks inside the Top 15 nationally in efficiency for the first time in years.

Odom’s turnaround has been swift. Just months into his tenure as head coach, he’s guided the Cavaliers to a 9-1 start and a Top 25 ranking in multiple team ratings metrics. Virginia is poised to move past its first losing season in 15 years and back into prominence.

However, with a potent offensive formula, strong defensive principles, dominant rim protection and the breakout play of freshman point guard Chance Mallory, can the Cavaliers go up another level and reclaim elite program status in Year 1 under Odom? Let’s take a closer look.

Offense: Checking The Numbers

Through the first 10 games, Virginia’s offense has hummed. The Cavaliers have scored at least 1.05 points per possession in every game this season, and in all nine victories, Odom’s team has topped 1.15 points per possession. With a talented, experienced roster, Virginia appears to have gelled quickly over the offseason.

That production also reflects Virginia’s underlying approach. Much like Odom’s VCU teams, the Cavaliers employ a math-friendly offensive system.

Virginia ranks inside the Top 65 nationally in 3-point attempt rate, with nearly 46 percent of its field-goal attempts coming from beyond the arc. The Cavaliers can space the floor at all times with four or even five shooters, and that 5-out spacing has opened driving lanes and increased rim pressure. According to CBB Analytics, just 4.8 percent of Virginia’s field goal attempts have been 2-point shots from outside the paint — one of the lowest rates in the country.

More paint touches naturally lead to drawing more fouls, and Virginia is getting to the line at a healthy rate. Led by power forward Thijs De Ridder, who draws 3.6 shooting fouls per 40 minutes (96th percentile), the Cavaliers are drawing 9.5 shooting fouls per 40 minutes overall. That’s up from 5.6 last season and puts Virginia on pace for its best mark in the CBB Analytics database, which dates back to the 2018–19 season.

That’s a massive jump from last season, one that has fueled a free-throw attempt rate of 41.5 percent. If it holds, that would be Virginia’s best mark in more than a decade.

While the schedule hasn’t been super tough, Virginia is also overwhelming opponents on the offensive glass. Each member of the foreign exchange frontcourt rotation — Johann Grunloh, Ugonna Onyenso and De Ridder — owns an offensive rebound rate north of 10 percent. As a team, UVA has corralled 41.9 percent of its own misses, a Top 5 figure in Division I hoops.

Those extra possessions are a key source of rim attempts and additional chances to draw fouls. According to CBB Analytics, Virginia has converted 70 percent of its put-back attempts this season, a rate that ranks in the 83rd percentile nationally.

The De Ridder-Grunloh pairing, in particular, has been devastating. With both on the floor, Virginia is +138 in 174 minutes, scoring 134.1 points per 100 possessions (99th percentile) with a net rating of +47.6 per 100 possessions (100th percentile). The Cavaliers have dominated the offensive glass in those minutes as well, rebounding 46.5 percent of their misses. That success has carried over against stronger competition, too: in 65 minutes with De Ridder and Grunloh on the floor against Northwestern, Butler, Texas and Dayton, Virginia has posted a 46.9 percent offensive rebound rate.

Early Offense: What’s Working?

Virginia’s offense begins with its willingness to run and attack in transition or early secondary offense. More than 15 percent of UVA’s field goal attempts have come in transition, a push sparked primarily by Chance Mallory and Dallin Hall. As the team’s lead ball handlers, they set the tone, but nearly anyone on the roster from positions 1-4 is capable of grabbing and going or advancing the ball with a hit-ahead pass.

Mallory, in particular, is electric with the ball. With an advanced combination of strength and speed, he’s capable of getting to his spots in the half court, and the challenge of keeping him out of the paint only becomes more difficult when he’s flying downhill in the open floor.

Both Mallory and Hall average more than two assists on made 3-pointers per 40 minutes, underscoring how effectively Virginia turns pace into perimeter production.

These transition opportunities are also especially important for Jacari White. A prolific, quick-trigger 3-point shooter over three seasons at North Dakota State (40.6 3P% on 11.2 3PA per 100 possessions), White has thrived in Odom’s system. He’s shooting the leather off the ball this season: 105 points on 69 field goal attempts, including 50.9 percent from deep (27-of-53 3PA).

White’s shooting will likely regress somewhat and come back down to Earth over time, but he’ll remain a consistent deep-range threat all season. Alongside Mallory, he anchors a reserve backcourt that stretches defenses and adds another layer of offensive firepower to the rotation.

Mallory has assisted on nine of White’s made field goals this season — the most of any teammate — and Virginia is +102 in 142 minutes with the two on the floor together. In those minutes, the Cavaliers have shot 45 percent from 3 and scored a blistering 141.7 points per 100 possessions.

The Cavaliers are averaging 16.5 seconds per offensive possession this season — a pace that would be the fastest in program history by a wide margin, according to KenPom’s database dating back to 2009–10. Adding fuel to the fire, Virginia has shot 39.8 percent on 3-pointers in “chances” created with 20 or more seconds left on the shot clock, per CBB Analytics.

Another way Virginia leans into that tempo is through a package of early-offense actions, most notably Pistol, Drag and Wide.

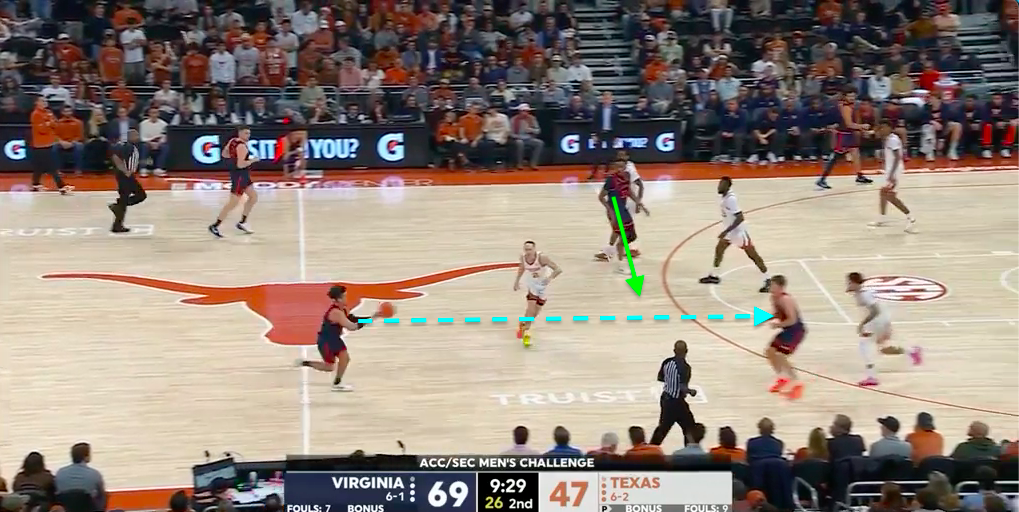

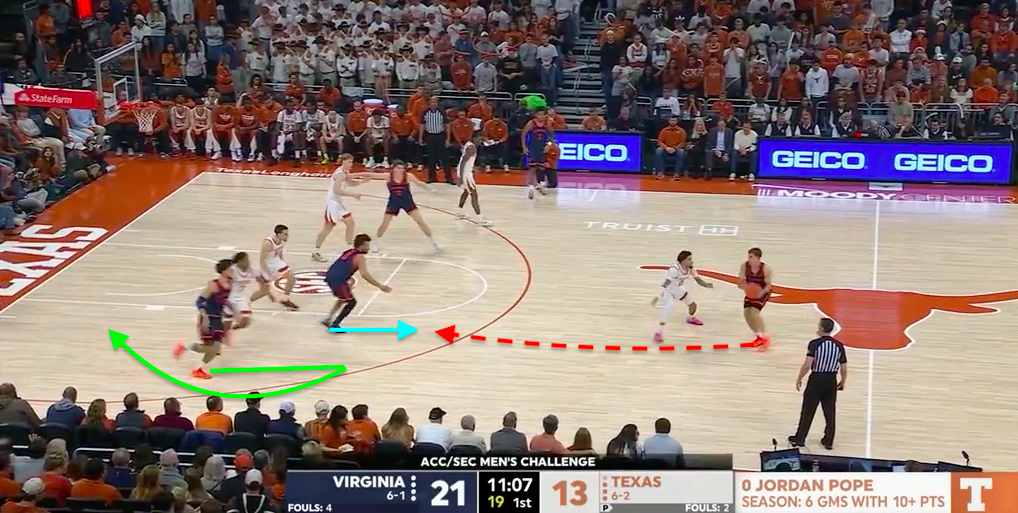

The foundation of Virginia’s Pistol series starts with one of the guards advancing the ball, a second guard spaced on the wing and the 5 positioned in the middle third of the floor. The ball handler triggers the action by passing ahead to the wing — something Mallory does here against Texas, hitting Hall — while Onyenso fills the middle at the top of the key.

Before the ball even leaves Mallory’s hands, he’s already sprinting in the direction of his pass. Hall quickly flips the ball back to Mallory, who now has a slight edge on his defender — thanks to Hall’s de facto screen and the added momentum. After the pitch-back, Hall comes off a flare screen from Onyenso toward the middle of the floor.

Texas guard Chendall Weaver recovers to get back in front of the ball, but Mallory has already turned the corner. Using his low center of gravity and tight handle, he chisels his way to the rim for an and-one layup. Mallory leads Virginia at 6.5 fouls drawn per 40 minutes this season, including four and-one finishes — third most on the team behind only Grunloh and De Ridder.

The forwards have a green light to operate in these Pistol actions as well. Earlier in the matchup with Texas, De Ridder (6-9, 238) and Devin Tillis (6-7, 240) replace Mallory and Hall. Tillis flips the initial entry pass back to De Ridder, and with Texas choosing not to switch, the Belgian takes advantage, spinning downhill and drawing a foul at the rim.

There are several reads Virginia can run off this initial action. For example, the wing player who receives the hit-ahead pass can fake a handoff back to the original ball handler and then dribble off a ball screen from the 5. That’s exactly what Sam Lewis (40 3P%) does here with Hall against Dayton, creating an open pull-up 3-point attempt.

Virginia will, of course, run Drag ball screens in early offense. The Drag pick-and-roll features the team’s 4s and 5s setting screens for ball handlers before the defense is fully set, often creating difficult rotations and communication breakdowns.

On this possession against Hampton, Malik Thomas pushes the pace, and the two defenders caught in the action are torn between drop coverage and switching the drag. The result: an open Onyenso on the dive.

De Ridder and Grunloh make for especially tricky coverages as drag screeners because of their ability to dive to the rim, short roll in space and pop out beyond the arc. When paired with a pull-up shooter like Thomas, Grunloh can slip into space and look for catch-and-shoot 3-pointers.

Grunloh’s long-term shooting projection remains a crucial swing skill. Looking back at his career in Germany, the statistical indicators were decent, but he’s clearly been encouraged to let it fly at Virginia. This season, Grunloh (30 3P% on 5 3PA per 100 possessions) has attempted at least one 3-pointer in every game.

Virginia’s Wide series allows the offense to flow into its sets through early off-ball movement. Wide action occurs when a player sets a high down screen at the top of the key, freeing a teammate on the weak-side wing to cut toward the ball.

UVA has run this action with De Ridder and Grunloh as the screener, with one key caveat: De Ridder will usually reject the screen and cut down the lane. From there, the point guard (Hall) swings the ball to Grunloh at the top of the arc.

When Grunloh receives the pass, Virginia can run a variety of actions off the initial refusal of the Wide screen. After passing to Grunloh, Hall sprints to set a down screen for De Ridder in the middle of the lane. De Ridder then flies off Hall’s screen and receives a handoff from Grunloh — the Zoom action from the middle of the floor. From here, De Ridder can look to attack downhill.

I refer to this as Virginia’s “Wide Gut Zoom” action, and it’s an effective way to get into the De Ridder-Grunloh pick-and-roll. It also creates a favorable switch for De Ridder (16.1 points per game on 55.1 percent shooting), who is emerging as a go-to force and matchup problem for opposing defenses. Put a smaller player on him, and he’ll go to the post (59.3 2P%); switch a bigger defender onto him, and he’ll attack off the bounce.

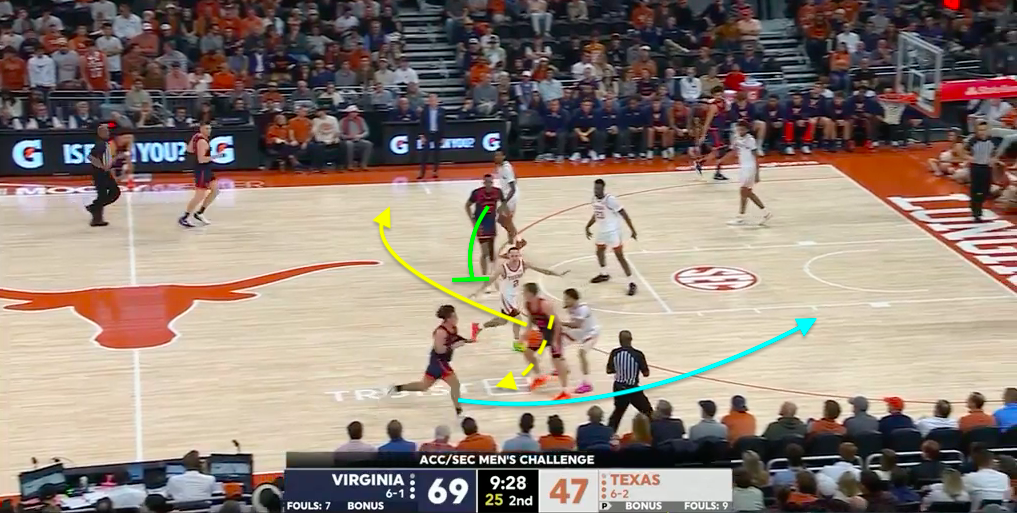

Later in the game against Rider, Virginia returns to its Wide series. This time, Thomas refuses the down screen from Grunloh, who pops and receives the entry pass from Hall, while De Ridder spaces out to the right corner. Virginia then flows into Flex action: Thomas sets a cross screen along the baseline for De Ridder, then comes off a down screen from Grunloh.

The Flex sequence frees De Ridder for a deep post touch and a finish at the rim.

Half-Court Offense: Pick-and-roll, Post-ups and Blind Pig

The days of Blocker-Mover and Inside Triangle as foundational half-court offenses for Virginia are over. While Bennett’s program had an incredible run leaning on these continuity approaches — with other creative sets mixed in — it was time for a change. Ron Sanchez showed hints of what might have come under Bennett last season, though he still relied on many of the tried-and-true methods of the past. Now, with Odom in Charlottesville, Virginia has a deep and diverse playbook.

This Cavaliers team will be a tough prep for opposing ACC coaches. Beyond the talent and ample 3-point shooting on the roster, they consistently target the right spots on the floor while running a variety of play types and formations.

Virginia’s offensive connectivity and ball movement are notable, too. De Ridder and Thomas lead the team in usage, at 25.2 percent and 26.3 percent, respectively. Along with Mallory and Hall, they drive much of the offense. But this team’s philosophy is to put defenses in a blender and attack from multiple angles. There are several high-feel players on this roster who can take advantage of a rotating by creating heady passing sequences after the initial advantage. The Cavaliers have assisted on 57.5 percent of their field goals this season, and six rotation players have assist rates above 11 percent.

Let’s take a look at three pick-and-roll types that UVA frequently runs (Angle, Empty and 3 Across), along with a few setups designed to get the ball into the hands of their frontcourt playmakers.

Angle

One of Virginia’s go-to pick-and-roll looks is the angled ball screen. This concept has grown in popularity, featuring a spread pick-and-roll look with a slot ball screen, opposite wing or slot spacing and two corner shooters. It’s designed to let the ball handler drive in any direction and open up the middle of the floor for the screener on a pop action.

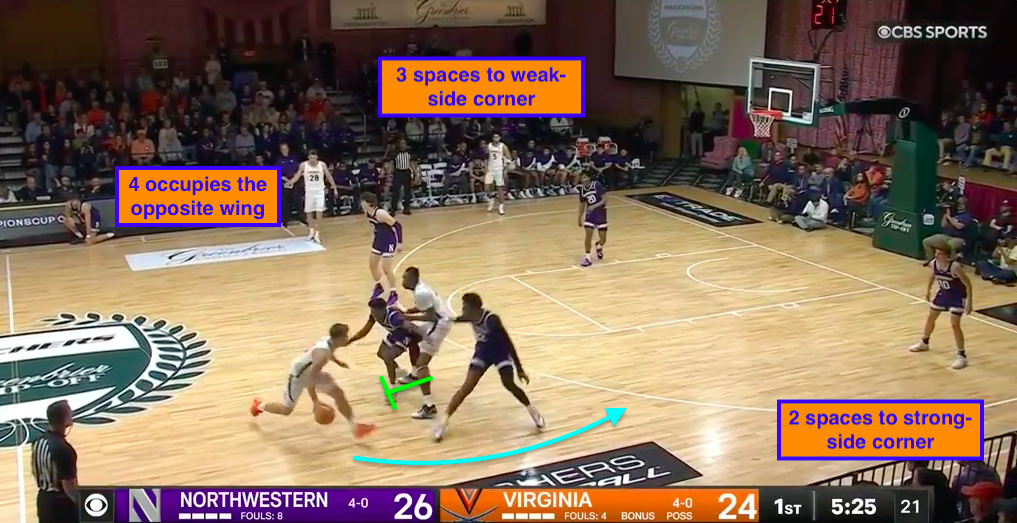

Hall patiently waits for Arriteng Page (who has been awesome this season) to retreat on his hedge before driving right off the screen set by Onyenso. Max Green doesn’t provide help off Thomas in the strong-side corner, which widens the driving lane for Hall even further. Meanwhile, De Ridder and Lewis maintain their spacing above the arc. As Hall picks up his dribble with two defenders on him, Northwestern’s weak-side defenders rotate back out to De Ridder and Lewis, leaving Onyenso wide open in front of the cup.

When the 5 pops toward the middle of the floor, it can trigger a transition into 5-out offense.

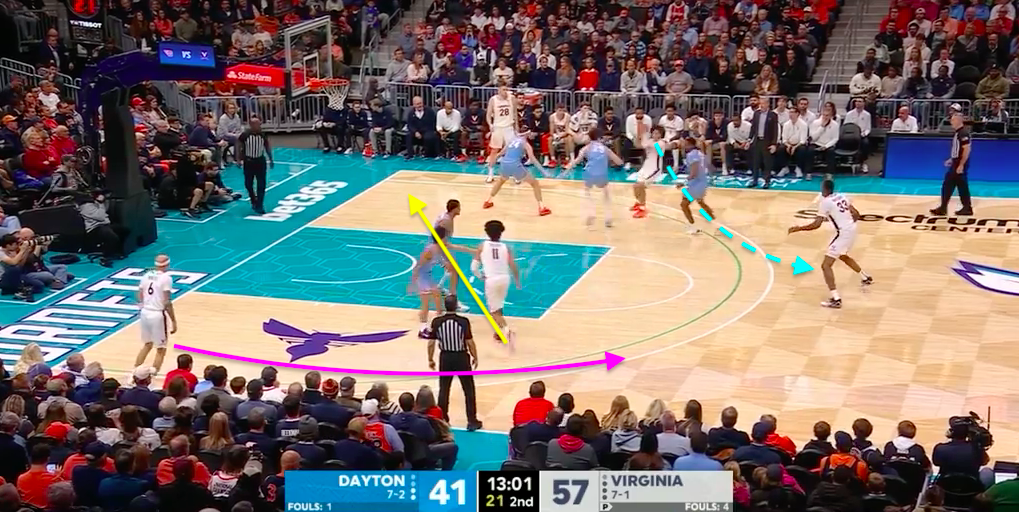

Here, Mallory and Onyenso run an angled pick-and-pop here against Dayton. The Flyers initially double the ball, but eventually switch the action, placing the 7-foot-1 Amael L'Etang on Mallory. Still, Onyenso is able to catch in space on the pop, allowing Virginia to flow into its 5-out offense. The pop prompts a 45-degree cut from Tillis, followed by White lifting from the left corner to run a pitch-and-chase pick-and-roll with Onyenso.

Dayton switches again and keeps the ball in front, but with L'Etang still switched on Mallory, UVA’s freshman guard snaps into action as an off-ball connector. Mallory sprints to the left side of the floor and flows into an impromptu give-and-go with White as he races by L'Etang’s helpless closeout and pulls in a help defender off the corner.

This savvy bit of playmaking craft adds to Mallory’s dynamism. He can initiate the possession, move off the ball and then — midway through the action — return to the ball to create open looks as a secondary, connective creator.

Empty Corner

If the initial action on a play doesn’t work for Virginia, the Cavaliers will often flow into an empty corner pick-and-roll: a ball handler and a screener on one side of the floor, with three shooters spaced to the weak side.

For example, this screen-the-screener baseline out-of-bounds play is designed to get the ball to Thomas curling to the corner for a 3 off a screen from Grunloh. Northwestern switches the initial screen with De Ridder and top-locks Thomas, preventing a clean exit off Grunloh’s screen. Virginia counters: Hall passes to Grunloh, and the Cavs run an empty-corner pick-and-roll with Thomas and Grunloh. As Thomas drives middle, he draws help from Northwestern’s Angelo Ciaravino, creating a kick-out opportunity to Mallory. Ciaravino scrambles to close out, but Mallory glides past him, attracts a help defender as he enters the paint and finds an open Grunloh in the dunker spot for the lob finish.

3 Across

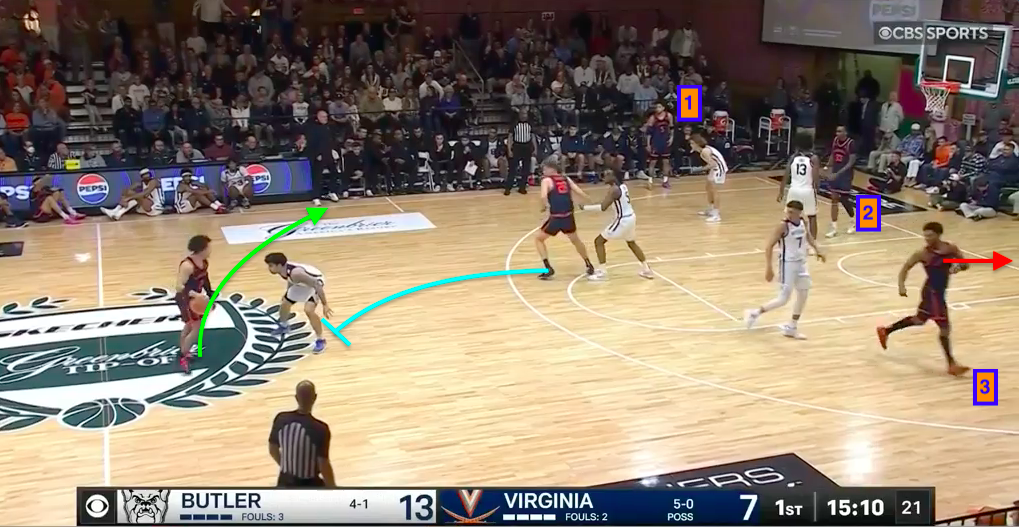

While Virginia runs numerous spread pick-and-roll actions — featuring three off-ball players spaced outside the arc — they also mix in plenty of “3 Across” looks. These sets position three players across the baseline: two shooters (Lewis and Thomas) in the corners and a big man (Onyenso) in the dunker spot, while two teammates (Mallory and De Ridder) run pick-and-roll in the middle third of the floor.

Stashing the 5 in the dunker spot keeps another defender in the paint, but it also opens up double-gap driving lanes on the ball side off the ball screen. With no offensive players spaced to the wings, the defense is stretched thin, leaving no natural help defenders in those gaps.

As Mallory drives left, he finds space thanks to Lewis pulling a defender toward the left corner. De Ridder’s role as a screener further complicates things for Butler’s Michael Ajayi, who doesn’t want to stray too far from Virginia’s stretch-4 (42.3 3P%). This allows Mallory to turn the corner and attack the rim with little resistance.

Drayton Jones is caught flat-footed at the rim, seemingly unwilling to help off Onyenso and risk an easy drop-off pass.

De Ridder and Grunloh can also operate interchangeably in these sets. They can flip spots. Grunloh can space the floor while De Ridder seals the paint or cuts along the baseline.

On this possession, Virginia runs a 3 Across pick-and-pop action with Thomas and De Ridder against Northwestern. The play flows into a 4-5 pick-and-roll with De Ridder and Grunloh. Northwestern switches the action, with Page guarding De Ridder, who puts the ball on the deck and attacks downhill. The initial shot misses, but Virginia’s bigs crash the glass, and Grunloh taps it back in for 2.

Once again, Virginia’s ability to extend possession and score off second chances adds an important dimension to this unit.

Blind Pig

Odom will also utilize several of Virginia’s frontcourt players to initiate offense from different areas of the floor, running designed post-ups or operating through the elbow with De Ridder, Tillis and Lewis. One way Virginia creates high-post playmaking opportunities is with Blind Pig action.

Blind Pig is a Triangle Offense concept featuring a backdoor cut: the ball handler feeds the high post, and a third player cuts tightly off the post to receive a pass while darting to the rim, exploiting an overplaying off-ball defender.

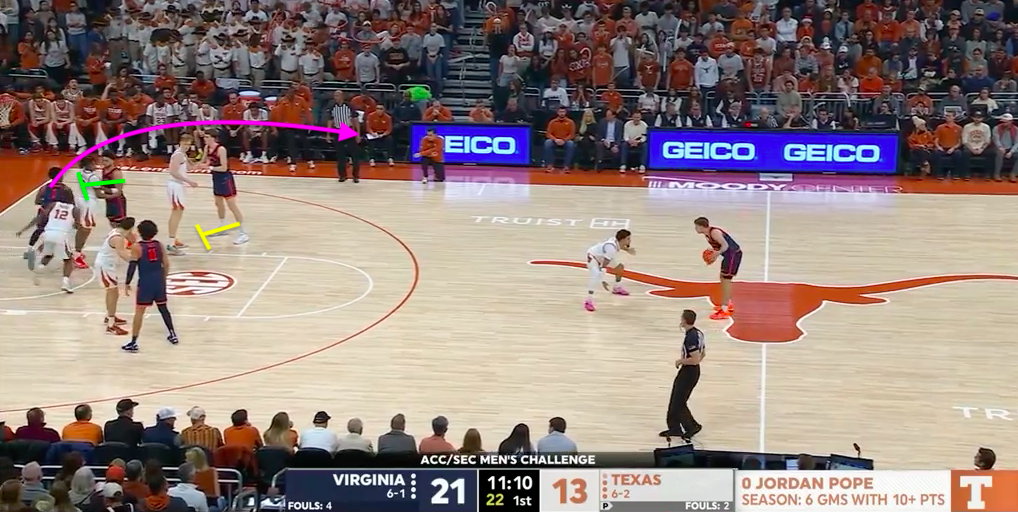

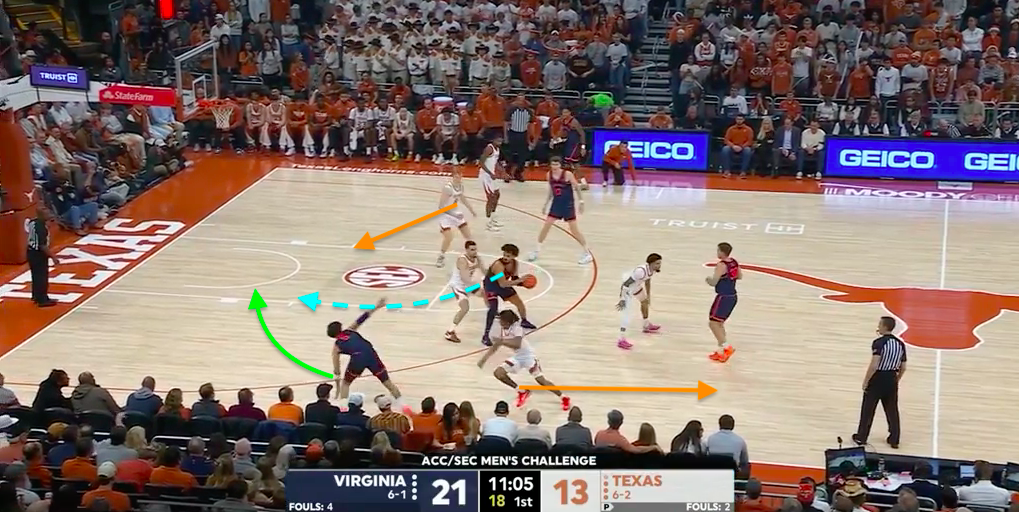

Virginia activates the Blind Pig by starting a half-court set with Floppy action: single-double down screen action for a player starting in the paint near the basket. In this after-timeout possession at Texas, Virginia sets up Floppy for Thomas, who curls to the right side off staggered down screens from Lewis and Grunloh.

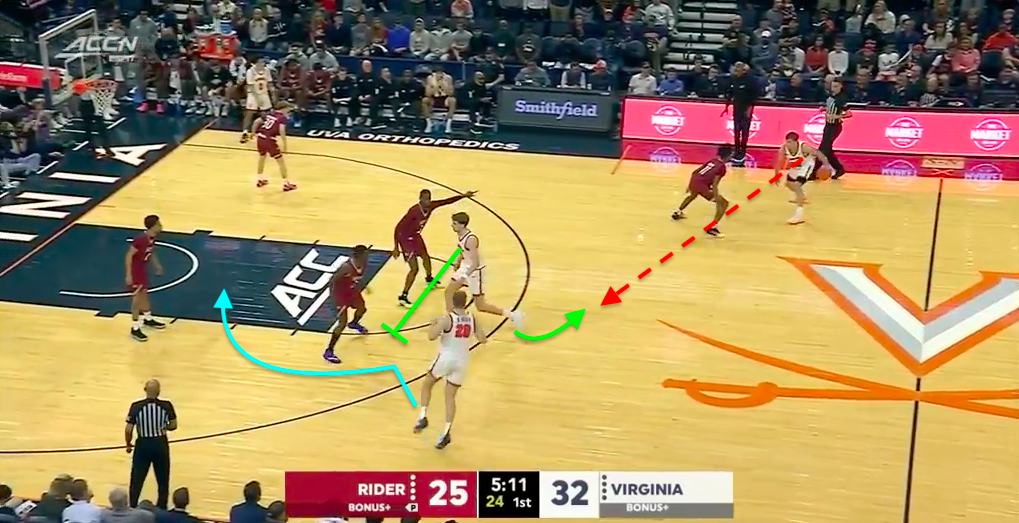

Hall initiates from the top and waits for Lewis to use the single down screen from Tillis just off the left side of the lane.

Before Tillis actually makes contact on the screen, he flashes to the high post, cutting up to the left elbow. Virginia now has a de facto 1-4 High alignment, ideal for the Blind Pig. Hall appears ready to pass out wide to Lewis, but instead feeds Tillis at the elbow. The Cavaliers have the setup they want, with Simeon Wilcher chasing Lewis and working hard to deny the passing lane.

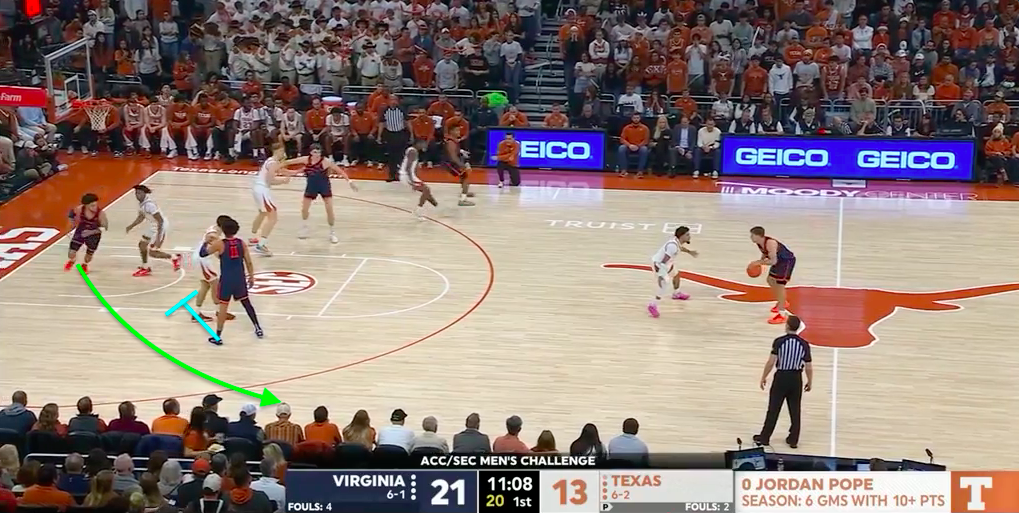

As Tillis receives the pass from Hall, Lewis slams on the brakes. Wilcher is left chasing air as Lewis pivots and cuts backdoor. This is the Blind Pig action in motion.

Tillis has plenty of space to flick a pass to the cutting Lewis, and with Grunloh lifted to the right slot, Virginia has pulled the weak-side rim protector away from the hoop. Lewis does well to stabilize, find his balance and finish through a late contest.

After a successful run of Blind Pig, UVA can leverage it from a play-sequencing standpoint. On the very next trip down the floor at Texas, the Cavaliers set up the same Floppy look for Thomas before flowing into a 1-4 High alignment. Instead of going to the backdoor Blind Pig, Tillis initiates 5-out Zoom action, with Thomas cutting off a down screen from Grunloh into a handoff with Tillis. Texas neutralizes any potential advantage by switching. However, late in the shot clock, UVA runs a pick-and-roll with Lewis and Grunloh; Texas puts two defenders on the ball, and Lewis finds Grunloh for a dunk on the short roll.

The Cavaliers do a lot on this single possession, shifting fluidity from one read to the next.

Virginia can also create different looks and shapes off the initial Floppy set. In the second half against Butler, White comes off staggered screens from Hall and Onyenso, followed by Hall lifting off a single down screen from Tillis. Instead of moving to the high post, Tillis sets a screen and seals in the mid-post for an isolated touch.

Tillis and Hall display their patience and experience as Tillis kicks it out, re-posts and spins off for a layup after another entry pass from Hall.

Defense: Focus In The Paint

The foundation of Virginia’s defense under Odom is a commitment to protecting the rim. Opponents are shooting just 53.9 percent at the rim against Virginia (95th percentile), per CBB Analytics, and with Grunloh and Onyenso platooning at the center position, Odom gets 40 minutes per game of elite rim protection.

As a team, Virginia ranks No. 3 in the country with a block rate of 17.9 percent. Both centers rank inside the Top 20 nationally: Grunloh at 12.6 percent and Onyenso second in Division I at 17.2 percent.

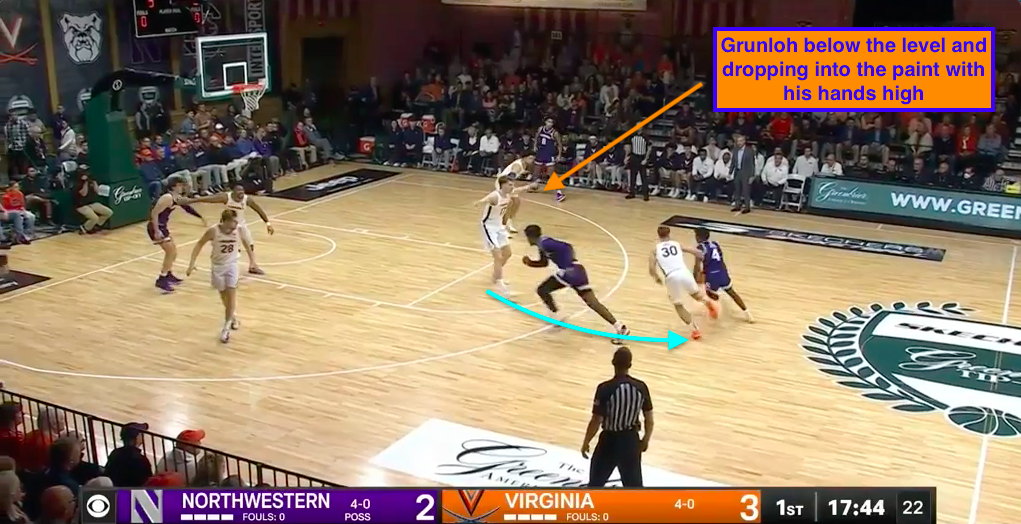

UVA’s defense will switch 1-4 and 4-5 to keep the ball in front. Against pick-and-rolls with the 5 as the screen defender, the Cavaliers occasionally mix in different coverages, including hard hedges. However, their base 1-5 pick-and-roll defense features drop coverage, with Grunloh or Onyenso positioned several feet below the level of the screen.

The goal of drop coverage is to keep the defensive 5 back, positioned between the ball and the restricted area. When executed properly, it makes straight-line drives and rolls to the rim more difficult. Grunloh demonstrates this here, maintaining his balance as he navigates the neutral space between Jayden Reid’s drive and Page’s rim run.

In theory, drop coverage should also help defenders outside the action stay closer to their assignments, reducing kick-out 3-point attempts. Opponents have assisted on fewer than 47 percent of their field goals against UVA. This is a trend that’s followed Odom from Richmond to Charlottesville. Moreover, only 32.4 percent of field goal attempts against Virginia this season have been from beyond the arc — a Top 25 mark nationally — which creates a significant delta when compared to Virginia’s offense (45.7 percent).

According to EvanMiya.com, Virginia ranks No. 2 in the country with 17 “Kill Shots” — the number of double-digit scoring runs the team has recorded this season. Duke leads the nation with 18.

Currently, the Cavaliers are winning the possession game thanks to strong offensive rebounding and turnover avoidance (No. 58 nationally in TOV rate), averaging nearly two more field-goal attempts per 40 minutes than their opponents. Within those possessions, Virginia is also winning the efficiency battle, taking higher-quality shots on offense while forcing opponents into difficult 2-point attempts late in the shot clock.

According to CBB Analytics, 16.7 percent of opponent field-goal attempts against Virginia are 2-pointers from outside the paint, and only 33.1 percent of 2-pointers scored on Virginia’s defense have been assisted.

Looking closer, 28.1 percent of opponent offensive possessions last between 20 and 30 seconds — ending in the final 10 seconds of the shot clock — which ranks among the highest rates in the country. On these plays, opponents score just 0.67 points per chance (82nd percentile), shooting 34.1 percent on 2-point attempts and 21.2 percent on 3-point attempts.

Of course, even if an off-dribble midrange 2-pointer is a less efficient shot, the defense still wants it contested. It falls on the on-ball defender to fight over the screen and apply pressure from behind. This is where UVA benefits from a roster full of players 6-foot-3 or taller, weighing around or above 200 pounds. Mallory is the one exception among the team’s perimeter players and he’s a force here, too, with his combination of lateral quickness and physicality. Top to bottom, they have the length and strength to disrupt shots in rearview pursuit.

Raising The German Flag

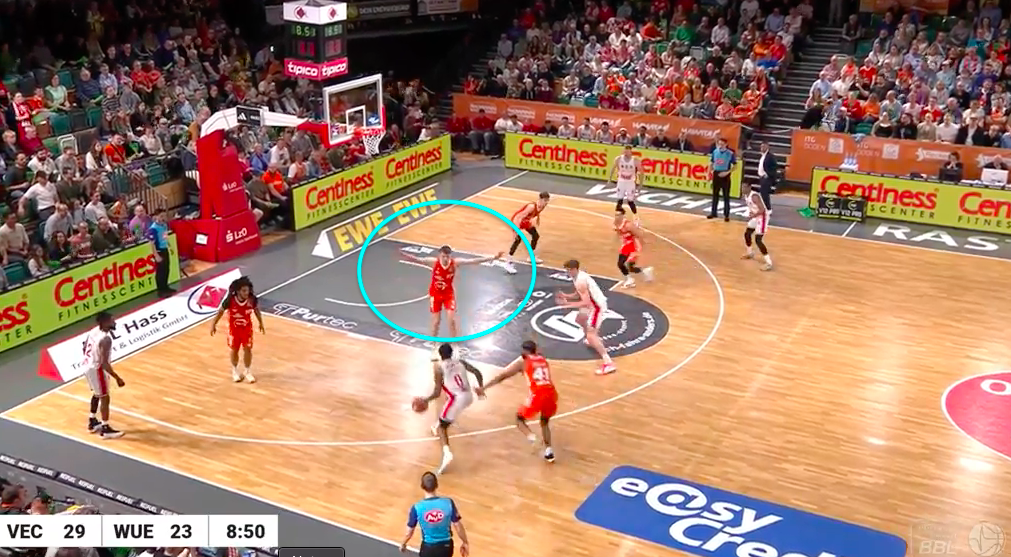

When I scouted Grunloh’s film with SC RASTA Vechta over the offseason, one of my favorite micro skills of his defensive profile was his hand placement on pick-and-rolls in drop coverage. Many defensive centers fail to maintain a proper stance with an athletic base, often complicating matters by keeping their hands low at their sides.

Grunloh is the opposite: he keeps his hands high and outstretched, making himself as big as possible and taking up maximum space against an oncoming driver.

He reminds me a little of a volleyball player in a defensive stance at the net: hands up, ready to leap and block a shot at a moment’s notice. The same principle applies on the basketball court for Grunloh. In these tight-space situations, where every inch and fraction of a second counts, his hands don’t have to travel far to get into position.

That approach has crossed the Atlantic, traveling from the Basketball Bundesliga to the Blue Ridge Mountains. I’ve charted eight of Virginia’s 10 games this season and have credited Grunloh with eight rim-protection blocks in drop coverage situations alone, including this rejection against Butler.

Beyond his hand placement, Grunloh demonstrates strong verticality and timing on his block attempts. He excels at high-pointing the ball, attacking it while the offensive player is already in the air. This makes him an effective deterrent against powerful downhill drivers, such as Daily Swain (62.8 2P%) of Texas.

Amping Up The Pressure: Chance Mallory

Again, Virginia’s defensive priority is protecting the rim. The Cavaliers will occasionally apply full-court pressure as well, though this tactic appears aimed more at forcing opposing offenses to burn 8-9 valuable seconds bringing the ball up against a man-to-man press than at generating turnovers. Opponents are averaging just 18.6 seconds per offensive possession against Virginia, one of the slowest rates in the country.

While Virginia boasts excellent size and strength throughout its roster, the team’s most impactful on-ball defender is the 5-foot-10 Mallory.

Mallory’s ball pressure is highly disruptive. It creates mistakes and gums things up for the opposing offense, occasionally forcing teams to set screens in the backcourt just to clear the time-line and initiate their sets.

The freshman point guard has been a revelation for Virginia, capable of heating things up at the point of attack while also helping clean the glass. Mallory ranks third on the roster — behind only Grunloh and Onyenso, the two 7-footers — with a defensive rebound rate of 15.4 percent. Currently, he is the only High Major player under 6 feet with a defensive rebound rate of at least 10 percent.

Virginia’s team steal rate sits at 10.0 percent, a solid figure but not elite. That changes when Mallory is on the floor: with him playing, UVA’s steal rate jumps to 11.3 percent, compared to 8.3 percent with him on the bench, per CBB Analytics.

Mallory leads all High Major freshmen with a 5.4 percent steal rate — a number impressive enough to usurp Reece Beekman, the defensive standout from a previous generation who excelled at generating steals both on the ball and in passing lanes.

What Mallory lacks in height, he makes up for with exceptional defensive anticipation and lightning-quick hands. His steals also fuel Virginia’s transition offense, directly leading to points, including this sequence where Mallory initiates a quick passing chain: Mallory to Lewis to an open Hall for a 3-pointer.

Through the first six weeks of the 2025-26 season,, Mallory is one of six High Major rookies with a steal rate above 4.0 percent. He’s joined by several intriguing guard and wing draft prospects, including the fast-rising Kingston Flemings (Houston), Killyan Toure (Iowa State), Ivan Kharchenkov (Arizona), Kayden Mingo (Penn State) and Dame Sarr (Duke).

Ready For The Leap?

This team is deep and talented, boasting nine legitimate rotation players and significant lineup versatility. If Virginia’s offense continues to perform as a Top 20 unit, the Cavaliers are going to win a lot of games. KenPom’s projection system has Virginia favored in all but three contests on its schedule: road trips to NC State, Louisville and Duke.

There are also clear opportunities for this team to round into even better defensive form. Those opportunities begin on the defensive glass. Odom’s defense has allowed opponents to rebound nearly 30 percent of their misses this season. That isn’t disastrous, but it sits around No. 150 nationally and trails other elite ACC programs such as Duke, Louisville and UNC.

Virginia is also fouling too often. Four rotation players — De Ridder, Grunloh, Thomas and Mallory — are committing more than four fouls per 40 minutes. As a team, UVA has allowed 8.0 shooting fouls per 40 minutes, a significant departure from the Bennett-backed defenses.

If Virginia can make strides in these two areas, it should be able to improve on the margins while maintaining what’s already an appealing statistical profile.