If we did subtitles, the subtitle would be "not in your lifetime," and this is true. This piece is written for those logging on in the year 2076, perhaps wondering what all the fuss was about 50 years ago, when your grandfather (age 83) was convinced that college basketball was dying and that college sports in general were going the route of the dodo. That may sound outlandish to you, so on your futuristic computer, whatever those may look like in 2076, you begin searching and land on this article from 50 years prior.

This must be funny for you to read, because in 2076, college basketball is still alive and well. It probably doesn't look exactly like it did in 2026 - hard for me to say, really. You may be watching games through Twitch, if that's still around. But it's going to exist. The sport, despite existential, meaningful threats to its very core in every direction nearly every year, will still be alive and well. College basketball has always been dying. It remains alive.

College basketball has never been at risk of dying so much as it has been perpetually accused of betraying someone’s memory of itself. This has been the case for decades. The example writers usually reach for is the initial panic over the expansion of the NCAA Tournament from 48 to 64 teams, but it extends well past that. College basketball will not die, because it has been here before.

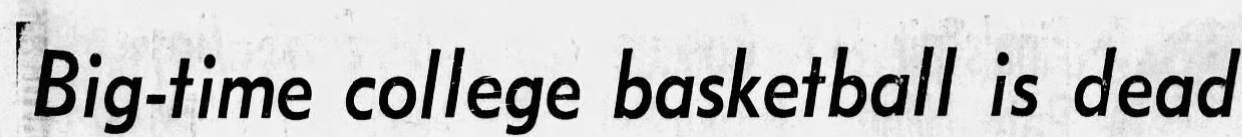

Fatalistic threats prior to the still-ongoing debate of the number of teams allowed in a postseason tournament may seem quaint in retrospect. In 1959, UPI writer Oscar Fraley, likely most well-known for writing The Untouchables, proclaimed that "college basketball is buried today in a morass of clutching, grabbing, and stalling which remains, and will remain, only because of the selfishness of the coaches." Fraley was referring to college basketball's refusal to add a shot clock, which wouldn't come for nearly three more decades, but it could be about any of the current supposed threats to the bottom line.

Fraley wasn't the first to try to bury college basketball, and he certainly wouldn't be the last. Go through old newspapers and records, and you'll find papers asking if college basketball is dying in the East, New York City, Pittsburgh, New York again, Birmingham, Portland, or just that, indeed, it is dead as of December 1973.

The reasons for these deaths were various. Certainly, the CCNY gambling scandal of 1951 had its effect on dampening the sport's reputation. 75 years from now, gambling scandals may seem quaint, but at the time, this plus other rumored scandals made college basketball look less like a wholesome campus activity and more like an appendage of organized crime. These moments gave the sport a seedy underbelly it's still struggling to shake all these years later.

Once professional basketball began to rise in the United States, cases such as David Brent (not the Ricky Gervais character), a 7-footer at Jacksonville University who left two years early for the ABA, became the latest end-of-the-sport fear to strike. Brent was one of the first non-seniors to leave college basketball early and was the first overall pick in the ABA's semi-secret college player draft in 1972 (only sophomores and juniors were selected). His rewards were becoming the face of a thing many were upset by - no less than future NBA logoman Jerry West said "college and pro basketball simply can't live together" - and receiving just $10,000 of his initial promised $1.1 million, being broke and out of basketball within a year of leaving school.

The same year Brent departed college for the NBA, the ACC athletic directors banded together to take a unified stand against undergraduates leaving college early for professional basketball. This is obviously funny to read in retrospect, but at the time this was written, it's just 54 years in the past. Think about it this way: the ACC banded together to stop early departures from college basketball more recently than the release of "Baba O' Riley" and the birth of Mark Wahlberg.

Brent's case is both timely (if only he'd been born 50 years later) and evergreen. Throughout history, though most notably the 1960s and 1970s, critics worried that college basketball existed only because pro basketball was still unstable. Once the pros became legitimate, college basketball would be exposed as a minor league pretending otherwise. Why watch amateurs if the real product existed elsewhere?

That argument sounds modern and is familiar to anyone with even a passing NBA fandom, but it predates the saturation of at-home televisions in America. (After initial skepticism that TV would have any impact, followed by hope for more than a few broadcasted games a week, TV would go on to also be viewed as a threat, as various college administrators thought it would destroy in-person attendance and nationalize a regional sport. As far as I can tell, only the latter has ever happened, and certainly not to the extent it has happened with college football.)

The ultimate case of moral panic in college sports is the event everyone loves most: the NCAA Tournament. It is younger (by one year) than the NIT and did not reach a doubling of the NIT's size (32 teams to 16) until 1975. For its first 15 years of existence, it was a clear second to the NIT and on roughly equal footing for the 15 to follow. Expansion was slow and steady for decades, then it happened all at once: 16 to 24 in the mid-1950s, 25 (1969-1974) to 32 in 1975, then the mega-rush: 32 to 40 (1979), 40 to 48 (1980), and finally, 48 to 52 (1983) to 53 (1984) to the famed 64 (1985).

At every single turn, these expansions were met with calls that the game was indeed gone. AP writer Bruce Lowitt claimed "in these days of rampant inflation, the word 'champion' has been devalued" once the Tournament moved to a 32-team field. Upon the news that the Tournament would expand to 40 teams, no less than John Wooden said he thought the Tournament was becoming "over-commercialized." Wooden got another opportunity to hate with his heart the next year, calling 48 teams "diluting the championships." (With all of this in mind, I would like to give the other side a representative voice: both Digger Phelps and Dean Smith showed themselves as consistent pro-expansion fans throughout the 1970s and early 1980s. The more you know.)

Nothing shattered hearts like the move to 64. My favorite old coach quote from John Gasaway's 'Keep March Mad' in 2025: “Have the gentlemen who run this spectacle lost their minds? Is the NCAA adding teams simply to give television more games?” Fast forward 40 years, of course, and 64 has become the preferred number of teams (more so than the 16 years of 68 teams in the field) because it fits the bracket format perfectly.

This is not meant to point that people in the past were always wrong. That would be the wrong way to look at essentially anything in life, even if, in the specific case of NCAA Tournament expansion, they were obviously wrong. It's meant to point out that every single decade, sometimes several times a decade, college basketball has faced threats framed as terminal to the sport. Writers did not say "this will change college basketball for the worse." They were more dramatic in saying that the sport would end.

In the last year, I went to Providence, RI for the first time to visit a friend and I went on a morning run. Towards the end, I looked up to figure out where to turn next and realized I was on Dave Gavitt Way.

For the lone member of the NCAA committee to vote against a 64-team field in 1983 to have not only his own street but his own games, it speaks to his impact beyond this one specific issue he felt negatively toward. To Gavitt's credit, he eventually acquiesced and became the head of the NCAA Tournament Selection Committee, perhaps making him the only committee head the average fan would know and approve of in 2026. Even people who were wrong about the future still helped shape it.

Gavitt is most notable for being the most prominent example in college basketball prior to social media of a widely beloved figure coming out against a widely beloved thing. He is also the rare example of a figure later backing down from his stance and supporting the thing instead of doubling down on being wrong. Most don't back down.

Championship-winning coach Al McGuire said college basketball was in a "steady decline", proclaiming "in 10 years the students will be picketing the coaches instead of the athletic departments." In reaction to the ABA news of 1972, the Arizona Daily Star's Rick Davis claimed "interest in college basketball will decline if a percentage of the best players sign pro contracts with eligibility remaining." Alternately, you could read this entire John Gasaway post from 2013, which offers a 70-year timeline of various talking heads proclaiming college basketball is not only in decline, but will be dying sooner than you think.

The common thread of all these complaints, whether the subject is saying it directly or not, is nostalgia for how things were. The belief, any time a perceived threat is afoot, is that college basketball was once in its correct, natural, morally coherent, and perfect form, which just so happened to be when I was a teenager getting into the sport, and we are currently drifting away from that pure thing. This could be and has been centered around any hot-button issue of its time, whether that was nationalized recruiting, a shot clock, the one-and-done era, or our current transfer portal situation where the average roster in 2025-26 contains just 25% of its minutes from the previous season.

Try a quick search with "college basketball" and your preferred negative descriptor next to it on Google. I went with "unsustainable," and in the last calendar year alone, it generates over 33,000 results. There are opinion pieces, YouTube videos, Reddit threads, Twitter discussions, and full interviews with coaches, all of which offer that the way things are headed in college basketball is unsustainable and that the end times are on our path if we don't turn around.

It may come as a surprise based on the tone of this piece that I actually agree with significant portions of the cultural concern. It isn't sustainable to continue refreshing 75% of your roster year-over-year. I would like to see more Zakai Zeiglers and Braden Smiths in my life who play for the same team all four years. While college basketball still has a greater depth of offensive and defensive systems than anything offered at the professional level, the slow death of zone defense does make me a little sad. When a player goes up for a thunderous two-hand jam to extend the lead to 6 with 1:30 on the clock, I would like the sense that he is doing this not only for himself, but for his teammates and the school he believes in, not because he was paid by an invisible collective of donors to do the job of dunking the basketball.

However, the difference between this set of beliefs and an actual "the sport is dying" belief is that the sport is simply objectively better on a nightly basis than it's been at any other point since I've been alive. Barring a shocking downturn in scoring over the final two months, this season (75.2) will have the highest points-per-game total since 1990-91's 76.7. Rebounding is the best it's been in a decade. There are fewer charges than ever. Several teams - Nebraska, Vanderbilt, Saint Louis - are having once-in-a-generation seasons that fans of those teams will remember for ages. Of the final three undefeated teams, one is Miami (OH), a team with one NCAA Tournament bid since Y2K.

The game that you and I grew up on may not exist, sure. But the game that you and I grew up on may not have been the best version of the game, either.

I think in these essays, you're supposed to make people think and even disagree with your points. My most disagreeable opinion in 2026 on a non-political level is that college football actually is dying. This is a complicated viewpoint to hold, because I still generally like watching the sport and I still like football. But looking down the road, youth participation in football is cratering. No sport in America has a lower return rate amongst youth ages 6-17, per Project Play, and even with combined flag and tackle football numbers, it is currently the youth of America's secondary sport. Basketball is first. This is despite participation in high school sports reaching record highs, meaning sports as a whole are probably safe.

Even beyond stats, the portal has actually affected my enjoyment of football in a way it has not in basketball. The product, right or wrong, feels like a watered-down version of the NFL. I cannot prove it, but I feel that everything writers have said for 70 years about the decline of college basketball and its 'dullness' is happening right now in college football. The season is now a month too long, and the depth and diversity of schemes has been greatly reduced. Even Army, famously the best example of a triple option offense, has evolved into a shotgun-based team.

The problem is almost certainly me. College football has moved on from the version that first made me feel alive, when I was 8 years old and running inside from a Christmas parade to see every fifth or seventh play from a Tennessee/Florida game. I no longer recognize the version of this sport that once made me feel young, and instead of grieving that, I’m declaring the sport unhealthy. I am what I criticize, and I own it.

College basketball has experienced all of the same changes and alterations college football has, particularly realignment, the transfer portal, NIL, and, yes, if it's a player or coach-led sport. However: instead of becoming a watered-down version of the NBA, the differences between professional and college play have actually extended. College offers fundamental differences - the shot clock, three-point line distance, various foul rules - but there is one that reigns above all.

In college, you can play the way Houston plays. In the NBA, no one has played the way Houston plays in 50 years. That is what I am looking for.

College basketball will not die, because it fundamentally cannot. The sport's survival doesn’t depend on purity, stability, or fairness. It depends on tension, and tension arrives every week, sometimes daily, during the course of any season.

The latest is Charles Bediako going from three-year G-League player from Alabama who had forfeited his college eligibility in 2023 to, all of a sudden, back on Alabama thanks to a state of Alabama judge (a major Alabama donor) ruling him eligible for 10 days. When this occurred, I will admit something: I freaked out. I thought this could be The Event, the one that actually does cause college basketball's enterprise to eventually fold in upon itself. Lest this appear as the most insane thing you have ever heard, possibly the smartest basketball writer on the planet, Sam Vecenie, said the same:

His attempt to return threatens to tear apart the fabric of the tenuous detente between the NBA and college basketball, which have long allowed the two groups to exist as separate, but mutually beneficial entities.

I think that Charles Bediako playing college basketball for Alabama in 2026 is a bad thing. Unless you are an Alabama fan, I do not believe this opinion is debatable. I also think that Charles Bediako playing college basketball for Alabama in 2026 could be exactly what college basketball needed, because this sport runs on tension, and tension was delivered to the maximum Saturday night as Alabama lost their first game with a three-time NBA contract holder on their roster.

.@blue_coats, you’re next pic.twitter.com/TKOgjlwAja

— Tennessee Basketball (@Vol_Hoops) January 25, 2026

It's very possible a lot of this will age poorly. Perhaps I am being too wishful in believing the NCAA can and will wiggle their way out of a jam with the Bediako situation. Then again, if they don't, there will be an adjustment, and there will be adjustments to the adjustment. If it didn't die before, it's not going to start dying now. The games are too good.

The thought of holding two opposing viewpoints at the same time and remaining fully functional is attributed to F. Scott Fitzgerald from 1936's The Crack-Up. Perhaps ol' F. Scott should've stuck around until 2026.

I believe that college sports are in a bad spot, but college sports (particularly basketball) are also in a great spot in terms of entertainment. (The TV ratings would certainly back this up.) If the NCAA Tournament expands, it will devalue the regular season to some extent, but the NCAA Tournament will remain the peak of a college sports entertainment product, never to be topped. I believe rosters are reaching a point of no return with regards to being built for the transactional, but the transactional behavior is creating some of the best basketball I've ever seen at the college level.

The rules of the sport may change. The economics likely will. The language, and how we discuss the sport, may change. The typical powers will shift. It will be fundamentally different than the sport you and I grew up on and learned to love.

Almost everything else about the sport has stayed stubbornly intact. The games will always be there. The NCAA Tournament will always be there. The kids will always be there. Realignment will threaten, but you will still hate Tennessee if you grew up in Lexington and you will still hate Ohio State if you went to Michigan. The emotional root, the learned behavior, will always be there.

College basketball will not die. You know that, because you're in 2076 and not 2026, but someone had to say it.