On second chances.

At the 78th minute of a home match against Tottenham in an endless, awful February, Marcelo Bielsa’s final managerial move with Leeds United was to take Junior Firpo out of the game. A sparkling four-year run, complete with Leeds making it out of England’s second-tier Championship into the Premier League for the first time since 2003, was coming to an end. Given the stakes - threat of relegation, ownership upheaval, a heavily injured roster, and no investment in new bodies - it was probably good timing.

But this story is not about Bielsa, who is now the manager of the Uruguayan national team. It was, and always has been, about Firpo. Firpo was the one guy Leeds brought in that year, the lone signing in the summer transfer window, brought on only because Bielsa wanted some depth in a system that runs opponents and his own guys ragged. I know this because I am forced by law to remember the bad times for my teams.

It was September 2020. The shutdowns were still raging; people couldn’t figure out what they could or couldn’t do. Some things were coming back and some things were not. A lot of things about life I’d really grown to love had suddenly vanished into thin air, thin memories you could see but not touch or feel. So, on the advice of some of my closest friends, I decided to do something fairly radical that I’d put off for 10 years: adopt an international soccer team.

The lone thing that seemed to be on at all in the summer of 2020 was soccer. The German Bundesliga restarted in mid-May, England followed, and while there were serious worries about if college football would even be played in 2020, soccer was the one thing that looked somewhat normal. My body shudders at the memory of the ‘bubble’ for both NBA and NHL, and, worse, the fake fans in stands at baseball games.

Two of my closest friends, huge soccer fans, egged me on. One kept talking about a team named Leeds United that was “very fun and very wild.” My main complaint about soccer growing up was that there wasn’t enough action, and truth be told, that complaint still exists somewhat. But it was September 2020, we’d gone through several different full television series as a two-person-and-one-cat family, and frankly, there was nothing better to do. So that Saturday, I put on the Leeds match, an early-season fixture with Fulham.

I didn’t miss another that year outside of travel. I have fond memories of watching them play Chelsea on a December Saturday as the Tennessee/Florida football game went on in the background. On a January Sunday, watching them travel to top-six Leicester City and beat the Foxes straight-up. The game against Liverpool the same day the Super League news broke. Watching a bore draw with Manchester United an hour after my first half-marathon. It felt new, stupid, and beautiful all the same.

The next season was simply stupid and more stupid. Their hubris got the best of them, the team wore down, they didn’t win an EPL match until October, and the coach got fired. The guy who bore so much of that frustration and hate was Firpo, because he was the one guy not there to drag them out of the Championship. To me, and to a lot of people, he was the unfortunate, unwitting symbol of the demise of a short but wonderful era of hope.

Leeds would save themselves in ‘21-22 in dramatic fashion, but by May 2023, they were back down to the Championship. Nearly everyone, good and bad, was let go. The team was rebuilt from the ground up.

Nearly everyone.

At this point, you may be begging me to answer what in the world a post with 600 words on Leeds United soccer has to do with basketball. It’s because I’ve become obsessed with comebacks, second chances, and the idea of there still being time. Time can be good and bad, though, as everyone knows.

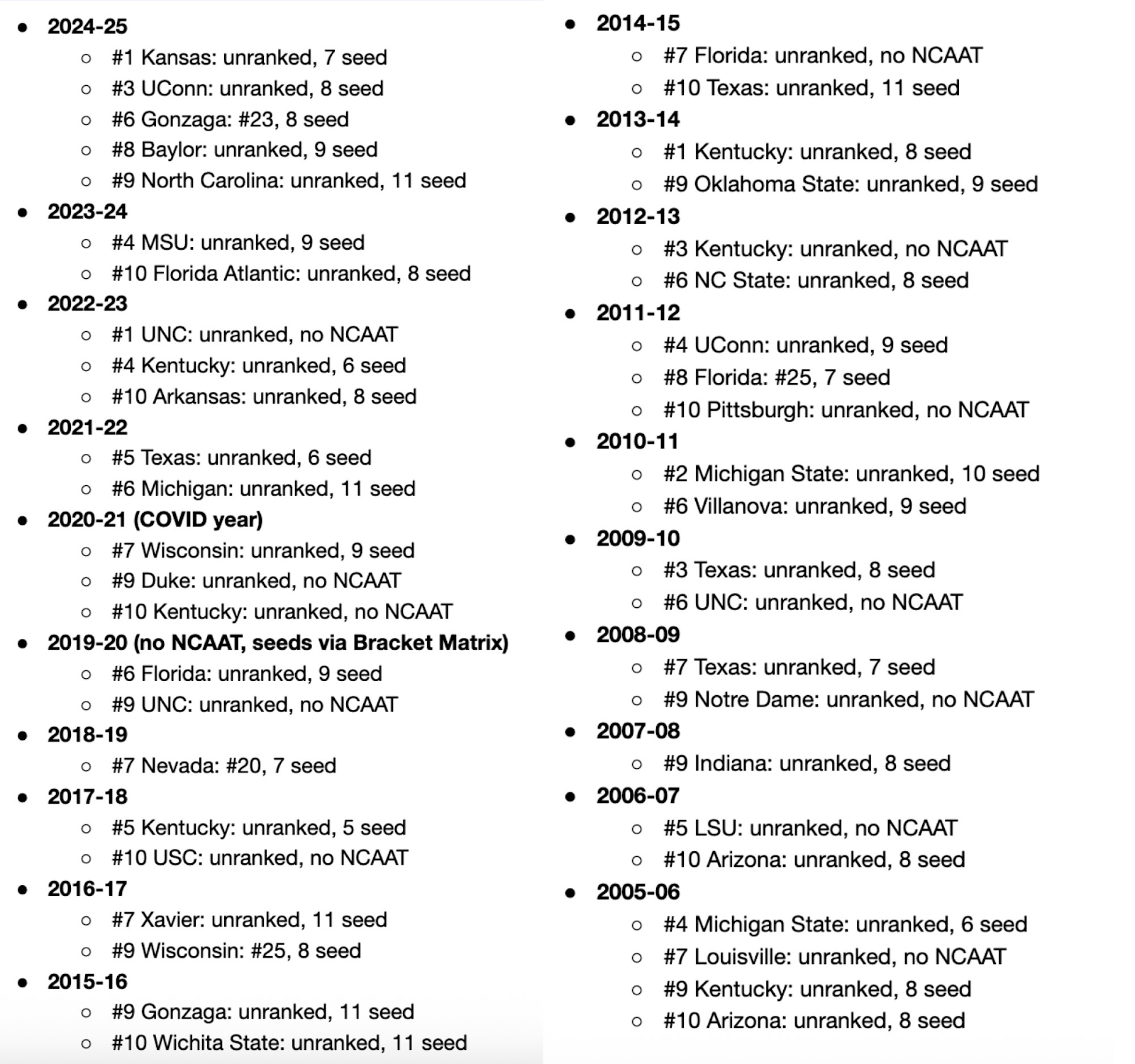

For someone who just got done writing about what to look for with teams who disappoint, it may come as a surprise that I generally don’t root for disappointments. I think it’s good when everyone succeeds, which is not the way life or any form of it works. Success is fleeting at best; failure is around you, everywhere, all the time. Look at this list of preseason AP Top 10 teams, just from the last 20 years, who’ve either finished unranked or in the 7 seed/lower range.

There are immense, deep failures here with numerous causes. Perhaps most interesting is that exactly one of these (2014-15 Texas) resulted in what they would result in elsewhere: the coach getting fired. (FWIW I don’t think you can count 2007-08 Indiana, that’s a completely unique situation.) In sports - really, in any field - the failures of an organization ultimately reflect on the organization’s leader. When a soccer club fails to meet their marks, it results in the manager getting dumped. The largest non-injury-influenced flops in the NFL (Cowboys), NBA (Suns), and NHL (Bruins) in 2024-25 all resulted in coach firings and new hires.

In college basketball, at least, it hasn’t been that way. When a team heavily underperforms its preseason expectations, the blame is placed on the coach, certainly. But because this is a sport where only five players can be out there together at once, the odds of the coach missing the brunt of the fallout because the players themselves attempt shots, box out, and defend is higher.

That list is not littered with fired coaches. In fact, some of the greatest coaches in the sport’s history - John Calipari (five times!), Tom Izzo (thrice), Rick Barnes (thrice), Billy Donovan (twice), Mark Few (twice), Jay Wright, Bill Self, Rick Pitino, Coach K, Mark Few, and even Dan Hurley - have flopped. Big time. But you don’t remember that the coaches flopped. The blame nearly always falls on the players themselves.

In the last decade, this has resulted in players with tremendous statistical careers like Hunter Dickinson, Dajuan Harris, Armando Bacot, RJ Davis, Kerry Blackshear, etc. being remembered as sources of frustration, not of joy. The most visible players of a failure end up being the ones remembered most, not the coaches who perhaps put them in suboptimal situations or schemes.

In the Portal Era, this has become even worse. Misplaced transfers - Coleman Hawkins at Kansas State, A.J. Storr at Kansas, Nicolas Timberlake at Kansas, Johnell Davis at Arkansas, Aidan Mahaney at UConn - become the reason a team doesn’t perform up to standards. We’re all rational enough to know it’s almost never Just One Guy, but as fans, it is profoundly hard to be rational in a way that suits us and the narratives we wish to craft.

Last year, North Carolina returned their starting backcourt from a 1-seed along with their top three bench pieces. They didn’t need to add much after getting two five-stars via traditional recruiting. They made two adds: Ven-Allen Lubin, a backup big, and Cade Tyson, a sharpshooter from Belmont who shared a roster with Ja’Kobi Gillespie and Malik Dia. Gillespie would be Maryland’s starting point guard on a 4 seed and is now the point guard for a preseason top-20 Tennessee. Dia: starting center for a 6-seeded Ole Miss.

Two of those guys played in last year’s Sweet Sixteen. The third played five minutes of a Round of 64 game and didn’t score in any of his team’s final six games. When it became clear last year that UNC wasn’t going to live up to expectations, blame went in many directions, a good amount of it to HC Hubert Davis. But a shocking amount of it went to one Cade Tyson, who became the face of a UNC team low on depth, lacking reliable wing defense, and desperately needing a prized transfer paid $700K to not shoot 29% from three.

Tyson’s quotes shortly after the season ended - “I'm just more disappointed than anything” - are pretty apt. Tyson is not alone. Last year’s three most wanted transfers - Oumar Ballo to Indiana, Johnell Davis to Arkansas, Coleman Hawkins to Kansas State - all experienced extreme disappointment. Ballo received death threats from Indiana fans en route to missing the Tournament. Davis struggled immensely for three months before finding himself in time to end his career in heartbreaking fashion after arguably his single best game in college. Hawkins, and Kansas State, buckled under the weight of immense dollar-driven expectations, ending the season in tears and tatters.

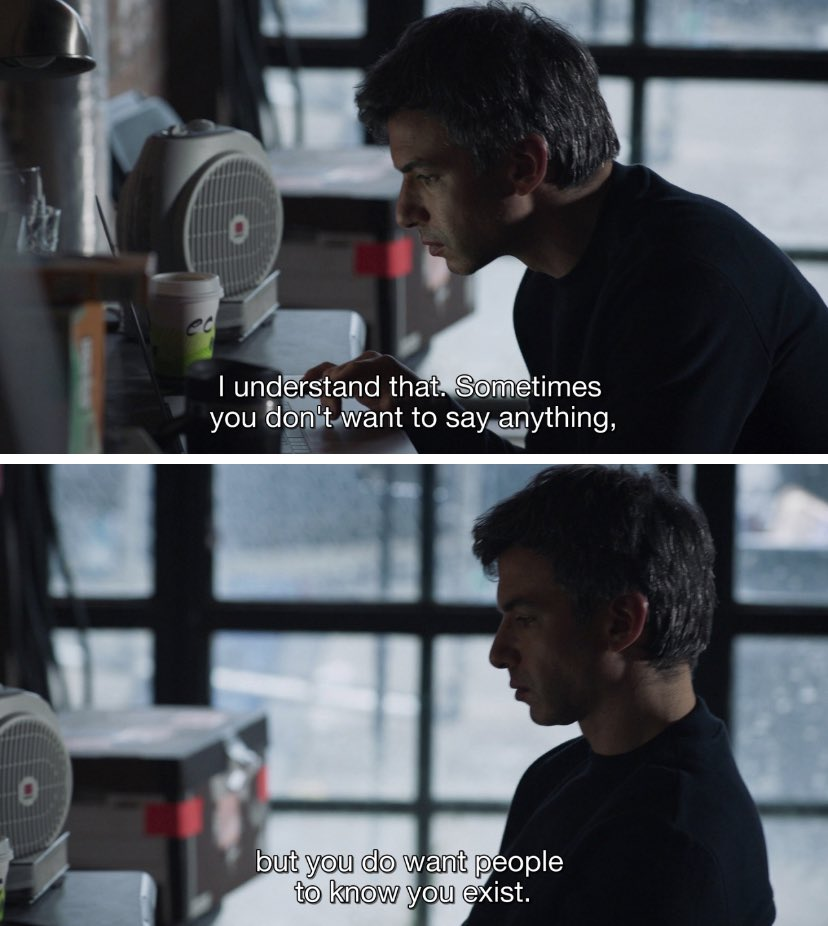

The reality is that it’s never Just One Guy. Deep down, we do know this, but in the moment, it’s tough to remember. I’m as guilty of this as anyone, as I wondered during the Round of 32 last year why RJ Luis couldn’t play better or how Hunter Dickinson simply couldn’t carry Kansas to greater heights. It’s easy to tell people to be better when you’re not out there yourself. Yet to say nothing at all leaves you in the dust in the take economy. As a genius once said:

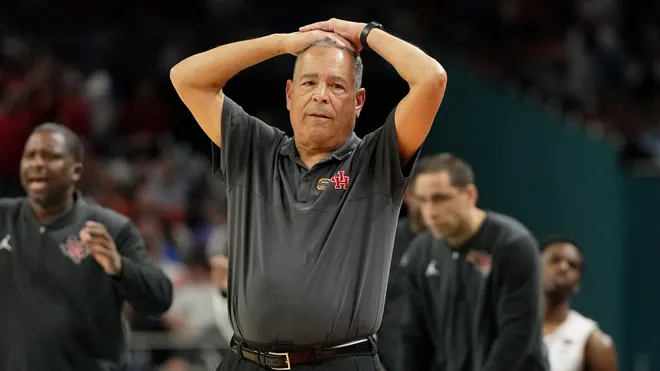

There are endless varieties of second chances everywhere you look. In this sport, the most famous second chance of the 2025-26 season will belong to Emanuel Sharp. After all, the 2024-25 season ended in his hands in perhaps the most crushing fashion anyone could imagine.

Sharp is a brilliant two-way player that has become massively underrated on a national scale. Everyone remembers how Sharp and Houston’s season ended; far fewer remember that Sharp scored nine of Houston’s final 15 points in their frenzied, historic comeback over Duke. Such is the dark side of sport, and of being the One Guy in a situation where so much more than one guy had to do wrong to get there.

The age-old wisdom of ‘one must fail before they succeed’ is a bit kinder than the reality. There’s a lot of failure in sport, but particularly in college basketball. This year, 365 teams, averaging around 14 players per side, will start the season with a goal in mind. At minimum, you want to make the NCAA Tournament. 297 will fail in this regard. You want to win your conference. 334 won’t do so. You want to be the last one standing. 364 teams, and around 5,000 Division I basketball players, will fail this season.

The question isn’t that they will experience a form of loss that hurts immensely. That question is answered before it even comes out of your mouth. The real question is this: are you willing to get hurt again?

College sports are brutal. You get four years, sometimes five, and then it’s over. Miss on your chance and another one may never appear. Unlike in professional sports, where you can hang on to the end of a bench for 20 years if people like you enough, you’re here for a short time, then not at all. Even then, the hurt extends pretty far for those who understand that time isn’t infinite.

There is no guarantee that, for instance, Houston will get to go to their third Final Four in six years and that Emanuel Sharp will become the first four-year player in Cougars history to play in multiple Final fours since Hakeem Olajuwon. The ball may never be in Darrion Williams’ hands again in the final minute of an Elite Eight game, and Williams himself won’t even be at Texas Tech. The heralded, beloved Purdue senior trio of Braden Smith, Trey Kaufman-Renn, and Fletcher Loyer is not guaranteed one final run at a national title. The winningest four-year players of the last decade are Josh Perkins and Corey Kispert, both of Gonzaga. For their efforts, they were rewarded with zero national championships.

It is easy to look at this and want to disappear, to be merely an extra in the background instead of being The One Guy. Some would rather have loved and lost than to never love at all; some know that joy and pain go hand-in-hand and you can only take so much in finite time. If Sharp, Smith, Williams, TKR, Loyer, and any of the other 3,000-ish players eligible for another year of college basketball who didn’t win last year’s title chose to move on out of fear of the director’s cut ending potentially being even worse, we couldn’t blame them. Gordon Hayward, the brilliant avatar of the greatest underdog of my lifetime, left for the NBA after missing his final shot of his college career. This one.

For 99.7% of the sport this year, and every year, it’s true: it always ends in a loss. (I guess now with four postseason tournaments of varying levels of legitimacy, you could say it’s more like 99% of the sport. Whatever, it’s a lot.) That’s a hard thing to stare down and be like “I want that.” There is nothing that guarantees your satisfaction in college athletics, particularly with tournament expansion, constant conference realignment, and other annoyances looming. I hear from time to time from people who have elected to take time away from it, if not leave it behind entirely. On one hand, I get it.

Alternately.

I want you to do a thing for me. It’s simple. Turn on your television, or better yet, go to a game this year and see it live.

There are these kids. They fight, and they play, and they orchestrate, and they push themselves beyond previously set limits daily. They are playing a game we have all played, one we all dreamed big dreams for in our youth. If I may steal a quote from a superior writer, they run like there is nothing in their pockets, nothing at all. They are the stars tonight, and of many more nights to come. If you’re watching correctly, it never truly ends in a loss. There is pain, yes, but there is joy, so much of it, along the way.

For the next six months, these players will chase impossible dreams. Some of them will turn them into reality. Almost none of it will be neat, and much of it will be a mix of horrible and beautiful. It's intoxicating, and there’s nothing like it. While we have it, let’s treasure it. And when the One Guy is on your team, perhaps consider zooming out a little. They've fought hard to be here. They want it, and they want the joy that comes with it, even if pain may follow.

In life, it can be nice to…just be nice. Y’know?

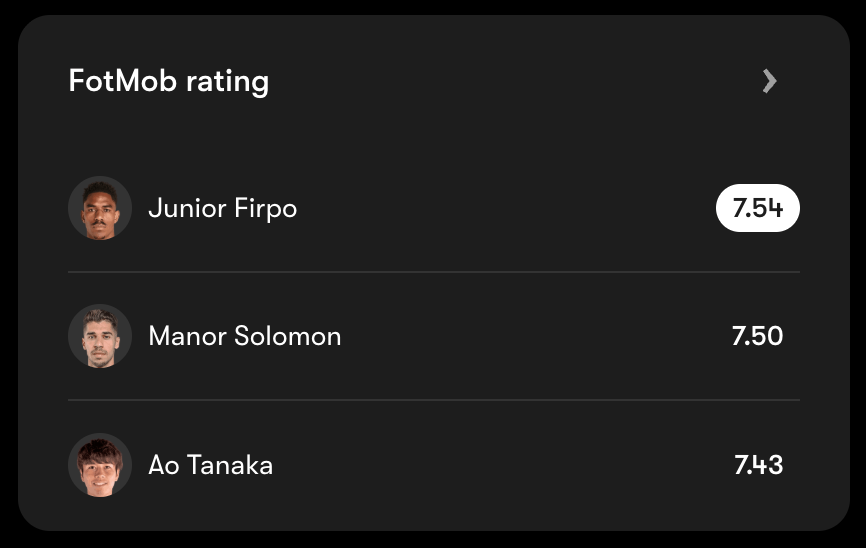

A funny thing happened in the last 18 months: by way of a complete career reversal in passing ability, tackling, and overall good movement, Junior Firpo became Leeds United’s best player. Well, by one measure, anyway.

Good enough for me. 2024/25 Leeds United set records left and right: the second-best goal differential (+65) in EFL Championship history, the most points (100) in club history, and an astonishing 17 consecutive league matches without a loss, their longest streak in 33 years. They clinched their fate, a promotion back to the Premier League. My buddy Patrick was there to see it. Given that the initial promotion from depths of despair occurred in the midst of peak COVID, it was like the celebration Leeds never got the first time around.

Celebrations, let alone spontaneous parades, are a source of great joy. It seemed very cool to me that in San Antonio, they let national champion Florida commandeer a riverboat to celebrate in perhaps the most unique way possible. In Leeds as the sun set that Monday night, it was seemingly the entire town showing up at the stadium gates. Drinks were had, players got recognized, all the usual stuff went down. Jobless at the time and five hours behind, I watched as much as I could and smiled all day. Yet I have just one photo saved from it: my favorite picture of anything in 2025.

Instead of burrowing inward the way many of us could and would, Junior Firpo stared down a terrible, desolate situation, said “I defy you,” and won. He is at his childhood club of Real Betis this season, career fully restored, and genuinely seems happier than ever. That is what belief, and the power of a second chance, looks like. That is the beauty of sports to me.

I don’t think that Cade Tyson, or his new team in Minnesota, are very likely to win the national championship, or any championship this year. They’re 16th in an 18-team media poll. The last NCAA Tournament appearance came in 2019. The odds of even a Tournament appearance, let alone a top-half Big Ten finish, are not too high. But it’s exhibition season right now, I saw this the other day, and out of nowhere I felt a strange mix of joy and pride come up.

Cade Tyson today against North Dakota

— Tony Liebert (@TonyLiebert) October 25, 2025

26 points

FGs: 9-13

3P: 4-6

4 rebounds

2 assists

He could end up being biggest transfer portal steal of the cycle.

pic.twitter.com/BSaYB1uvSk

When we make mistakes, all we can ask for is another chance. Sometimes, the path back for others is much clearer than for our own. Yet there’s always a path back, and when you take step after step on that path, the world lightens a little bit more. You’re not scared. You’re out of here.

I wish Tyson, Sharp, Williams, and all of these kids, all of whom run like there is nothing in their pockets, way more than luck. Let’s basketball.