During the pandemic, my wife and I cycled through a bunch of different shows and movies we had on our various watchlists but never had the time to go through. Suddenly, there was more time than we knew what to do with. The only show I can recall with much clarity from this time was Terrace House, which ended under horrific circumstances but was quite charming and relaxing from our viewing experience. I saw a Japanese young adult named Minori say a phrase that has removed birthdays and passwords from my brain to make room.

I myself can not live forever doing nothing, which is why I run marathons and get antsy when seated for more than 30 minutes, but I respect those who can. It's a great life if you can get it. Anyway, I guess I'm getting either nostalgic or old because I think about my use of time a lot. A good bit of this has been spurred on by my summer tradition of watching most Tigers games, but moreso because this video I watched a few weeks ago made me recall a tremendous tradition of my youth: objectively mediocre pitchers routinely posting 7+ inning outings.

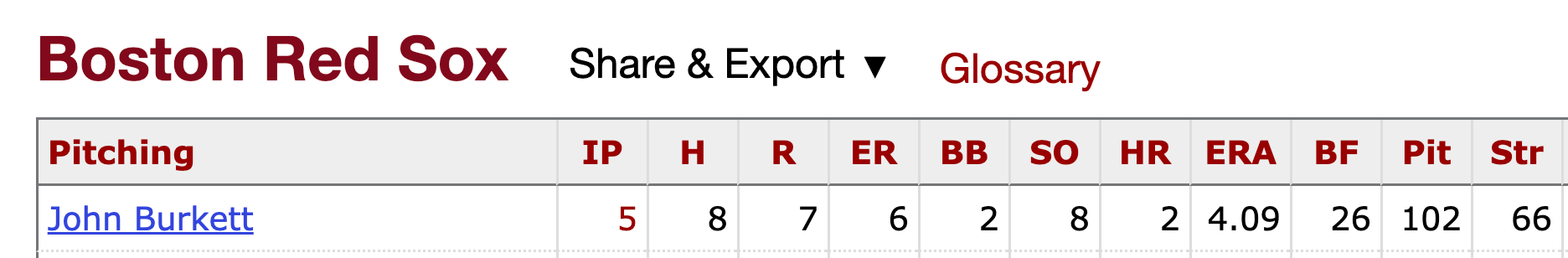

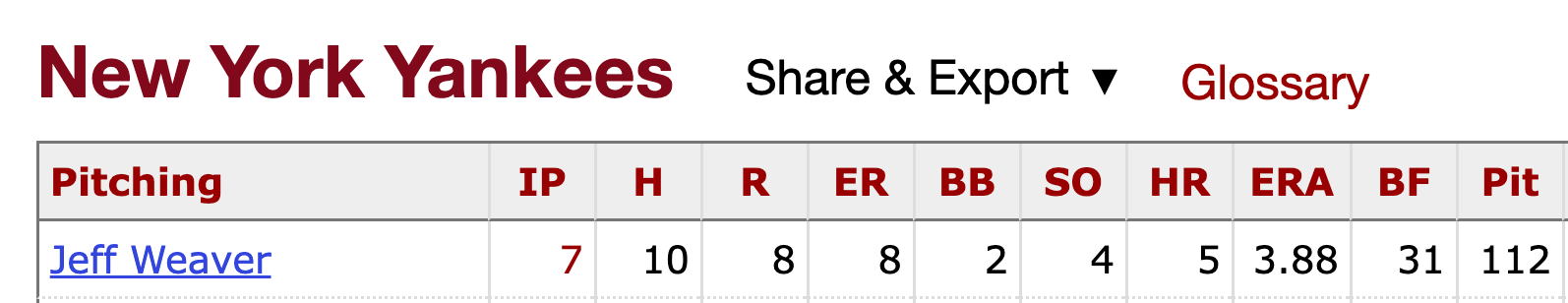

When I was a youth, I would watch baseball obsessively. I loved the numbers even at age nine when my grandfather was the lone 1950s-to-death Yankees fan I was aware of in rural Tennessee. Oddly, it's not any big play that stands out from this time; it's just the fact that guys went inning after inning almost regardless of what they did in said innings. Here is an effort from July 21, 2002, a randomly selected summer day that featured your standard long-as-hell Yankees/Red Sox affair. The two starting pitchers that night are two guys almost no one has thought about in at least 15 years.

Collectively, they gave up 18 hits, 14 earned runs, and seven homers. And yet: each got the chance to complete at least five full innings. The Weaver outing - 8 runs allowed in 7 innings, yet 31 batters faced - is particularly interesting. Here is the complete list, 2019 to present, of pitchers allowed to throw 110+ pitches, complete 6+ innings, and allow 7+ earned runs:

.

..

...

None. It hasn't happened in seven years. Now, this wouldn't be of interest to you or to anyone except this used to happen all the time. From 1999 to 2005, the same seven-year time period 20 years ago, the 6+ inning/7+ ER/110+ pitch trinity happened 77 times, with Jamie Moyer and Livan Hernandez being sort of the kings of the genre. (If you lower the pitch requirement to 100+, Moyer did it three times in a four-week span in 1999.) This staple of the game, the boring-but-space-filling innings eater, is mostly gone. Its essence still exists in spaces, as 2 WAR player George Kirby finished top 10 in innings pitched last year, but the GOATs of the game, the Mike Hamptons...they're long gone.

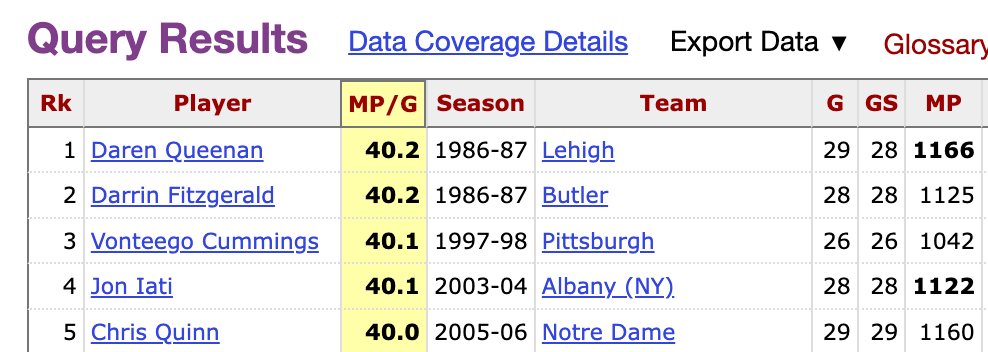

This phenomenon exists pretty much everywhere - football and its 30+ carries a night running backs being the main American comparison, or perhaps the nebulous load management theory - but an underrated one is that in college basketball, no one plays every single minute anymore. Usually. In the shot clock era, from 1986-87 through 2008-09, guys would play a truly bonkers amount of minutes. 62 players in that time span averaged 39 or more minutes a night, with this special fivesome topping 40.

From 2009-10 to now, that number's fallen to 8. Only 2013-14 Bryce Cotton of Providence has topped 39.5, and when a player plays every available minute in a game these days, it feels like a notable story rather than the expected norm for a team's top player. This isn't necessarily a bad thing, of course, because in theory it allows our best players to save some miles for when they need it most, but like the Chad Innings Eater, sometimes I do miss when a guy would go the full 40 (or even the full 45) in a non-conference game against Syracuse. It was cool.

Then, last season happened, there was a resurgence in endurance courtesy of one team in Iowa: the Drake Bulldogs. Drake was the only team last season, and just the fourth in the last 11 years, to have two guys average 38+ minutes a night. One of these players was fairly obvious in Bennett Stirtz, the best player and center of everything offensively. Generally, guys who play 38+ minutes are going to score a lot of points. Those who've done it since 2009-10 have averaged 18.1 PPG, 13.4 field goal attempts a game, and a 25.9% Usage Rate. Stirtz: 19.2 PPG, 13.4 FGAs, and 25.8% USG%.

Stirtz led the country in minutes. His teammate, this one with an active LinkedIn profile, an MBA, and serious Power BI skills, was the other 38+ MPG guy and #2 nationally in minutes per game. This guy.

Mitch Mascari had accepted a finance job in Chicago, making him approximately the 986,239th Midwestern college graduate to do so in the last decade. He had to call and tell his boss "sorry, my old coach Ben McCollum got a Division I job and he wants me on the team." Mascari's Division II career was solid - two titles and a pair of years as a starter - but his peak season of 10 PPG and roughly one shot attempt every 5 minutes, 17 seconds was not what one generally thinks of as a mega minutes-getter.

Yet there's Mitch Mascari, refusing to accept the end, because acceptance can be its own form of fatigue, and fatigue means you play less minutes. Instead, Mascari's decision to return and up-transfer after a quality role player career at the Division II level led to one of the most unique seasons I have ever seen. It does appear that in some sense, Mr. Mascari can live forever doing nothing.

Here, once again, are those stats on the 66 guys who've topped 38+ MPG since the 2009-10 season. On average, they go for 18.1 PPG, 13.4 field goal attempts a game, a 25.9% Usage Rate, 4.0 APG, 3.9 RPG, and take about 4.6 free throws a night. In rare seasons, a player will generate tons of minutes by way of no depth and/or not fouling - Kareem Thompson, 2023-24 Oral Roberts, he of 38.3 MPG, 12.4 PPG, and a foul roughly once every 25.5 minutes of game time. Usually, though, it's basketball, and basketball can be simple: if you're out there, you better produce points or keep your opponent from producing.

Here is where 2024-25 Mitch Mascari, the second-highest minutes getter in all of college basketball, ranked out of the 66 in each category mentioned.

- Points: 66th (9.4 PPG)

- Rebounds: 65th (2.2 RPG)

- Assists: 63rd (1.3 APG)

- Usage Rate: 66th (13.4%; next-lowest 18%)

- Field Goal Attempts: 66th (7.3 FGA)

- Free Throw Attempts: 66th (1.6 FTA; next-lowest 2.1)

In preparation for this article, I designed a very simple stat attempted to gauge what we're calling Minutes Eaten for college basketball. The equation is as such:

Available minutes played (Minutes%) - (Usage Rate * 2) - PPG - RPG - APG

Is it exceptionally simple and dumb, even for one of my articles? Well, yes, but that's the point. I want to spend no more time on it than I am legally required to. It has not been backtested whatsoever, which I figure is perfect for the level of seriousness displayed here. Basically, the thing I'm trying to get to is this: how many more minutes did you play over a reasonable expectation for someone with your stats?

By pure Minutes Eaten, Mitch Mascari ranks #1 in the last 20 years. I tried to slice the numbers a variety of different ways; the best I could get it to come out as is that Mascari played around 12 more minutes per game than would be expected from someone with his numbers. Even backdated to 2002-03 to get the largest sample size possible (99 players at 38+ MPG), Mascari has the lowest Usage Rate, the second-fewest field goal attempts, and the second-lowest PPG/RPG/APG sum (Marcus Schroeder, 2006-07 Princeton) of anyone to top 38 minutes a night.

In the Foolish Baseball video, a key item is noted: the average MLB baseball team must find a way to get a lot of outs in a given season. In 2024 specifically, the average team had to get 4,311 outs over 1,437 innings. For Drake, they had 30 regulation games and five that ended after one overtime. Considering the max one player can get in a regulation game is 40 minutes, that's 200 available minutes per night for regulation and 225 with an additional five-minute period. That totals out to 7,125 total minutes available for the Bulldogs in their 2024-25 season. Someone has to fill those minutes. Why not Mascari?

Now, it must be said that Mascari, beyond Power BI and XLOOKUPs, does have one strong plus skill: three-point shooting. At Northwest Missouri State, Mascari shot 165-378 (43.7%) from deep over his four-year career, along with 87.7% from the line on 114 attempts. Considering that only 26 players have ever done that in Division I, with only August Mahoney of Yale doing so in the last four seasons, that's a pretty attractive skill to have as a role guy.

Predictably, at the D2 level, a majority of Mascari's shot attempts came from kickout passes (usually via Stirtz) or stationary handoffs. His senior season at NWMSU saw 72% of his shots be stationary catch-and-shoot threes. Of course, when you shoot 48% from three and 49% on catch-and-shoot attempts specifically, it would be ill-advised for you to not mostly take those. Because Mascari so rarely shoots - again, once every 5.3 minutes, give or take - he had the ability to lull his defender to sleep at bad moments.

If you shoot 48% from three and 93% from the free throw line, you're probably going to get a good, healthy number of minutes. Such was the case for Mascari, who played 34.7 minutes a night for the Bearcats and barely left the floor in their final few games.

Even at the Division II level, though...well, how do I say that he rated out as a not-great defender? Out of 34 players who garnered 34+ MPG in D2 last season (min. 30 games played), Mascari rated 31st in Defensive RAPM at CBB Analytics, 25th in combined Steal%/Block%, and 29th in foul efficiency (your ratio of steals + blocks to fouls committed). While Mascari's Steal% of 2% was solid, it was actually the worst of the three players (Stirtz and Wes Dreamer) on NWMSU who played 34+ minutes a night.

None of this is a crime, obviously. Mascari is out there to shoot, not to be Ben McCollum's lead lockdown defender. But what it does do is create the obvious question: when Mascari is not attempting a shot, rebounding the ball, passing the ball, or doing some sort of defensive action, what is he doing on the court? If one were to go by pure actions logged - shot attempts, rebounds, etc. - Mitch Mascari did something on the basketball court that could be recorded by a statistician roughly once every 2 minutes and 7 seconds. Here is a possession where he is registered as Doing Nothing.

Except that Mascari does quite a bit here. Mascari is such a threat as a shooter that he requires an attentive defender at all times. Three days prior to the game featured here, he went 4-6 from three in a Tournament win over a decent Southwest Minnesota State side. You can see the momentary freakout from Minnesota State late in the clock when they realize they've missed the switch. They got away with it, but the effect of Mascari is that even when he seems to be doing nothing, he draws so much attention and brainspace that it requires you to do something as the defender. Sag off of him and you give up almost 1.5 expected points per shot. Stay too tight to him and you lose a critical piece in your attempt to stop the rest of the NWMSU attack, even in a relative down year for the McCollum offense.

Translated up to Drake, the appeal is pretty obvious. Having one of the most efficient deep shooters in the modern history of college basketball on your team works as a sort of cheat code, even when that cheat code posts a 10.8 PER and the lowest Usage Rate of any mega minutes-getter in history.

The Drake version of Mascari, the Greatest Innings Eater of All Time Or At Least the Last 20 Years, actually had a mildly down year of his own shooting-wise, hitting just 40.5% of his 3-point attempts and 82% of his free throws. Blame the job search in the back of his mind, I guess. Still, when this is below your historical expectations - 40.5% 3PT on 215 attempts, 82% FT in your first and only year of Division I basketball - you clearly still matter to the puzzle.

The Mascari role, loosely defined as 'dynamic shooting wing' at Synergy, is mostly this: help your Drake teammates run through Ben McCollum's motion-heavy, P&R-heavy structure, stay situated on the perimeter, and keep moving until you find a screen or a cut you like. In this sense, minus the gambling problem, Mascari is like a Missouri Valley Malik Beasley, moving off of screens and handoffs and even pick-and-pops in McCollum's highly effective sets. See the problem he creates here against Belmont, as an initial denial simply leads to reset after reset until Mascari finds his shot.

So, obviously, Mitch Mascari is not merely out there eating up time and space. He's doing as much as he can to help his team win, and shooting the way he shoots is a pretty big part of that. But, well, you saw the stats. What happens when the ball isn't in his hands?

Simply put, it depends. Some possessions, Mascari is setting picks at the top of the perimeter to get the Luka Doncic of Iowa free for a drive to the basket. This is not an event that registers in the boxscore, but it is objectively impactful and meaningful to the game.

Other possessions, though...well, Mitch Mascari eats minutes by nature. It's his job. When you play almost every minute of your team's season - 96.7% of them, in fact - you have to pick and choose which ones you go really hard for. Given that Drake played at the slowest pace in all of college basketball last year, what this can mean is simply occupying space on the court and being a decoy. Kerwin Walton, who has a smart basketball coach that knows Mascari averages 1.12 points per shot and an astounding 1.32 the year before, cannot leave Mascari for more than a second.

Obviously, this is just the countable stuff in the boxscore. Drake's general athleticism dictated their rules of the game, which is that Mascari (a great shooter, but probably not the greatest athlete) almost always rushed back to stop any transition play before it happened. Does this register in the boxscore? No, but given that Northwest Missouri allowed the fewest transition possessions of any team in D2 in 2023-24, followed by Drake allowing the fewest of anyone in Division I in 2024-25, it's probably pretty impactful.

In the halfcourt, Mascari seemed to be the target. Synergy credited him with being individually responsible for 58 more opposing shot attempts than any other player on Drake's roster. Unsurprisingly, a former D2 guy and future financier was not terribly good at keeping his opponents from beating him to the basket, sitting in the 49th-percentile overall in 1-on-1 defensive efficiency.

To Mascari's credit, he fouled only once per half on average, and Drake still had a top-50 defense with top-20 DREB%/TO% numbers despite having the 306th-best 2PT% defense. Mascari's role was to keep his guy in front of him, and considering 75% of the shots against him were jumpers, I would say he accomplished that.

If you look at all of that - a guy who knows the offensive and defensive structures, never fouls, is an excellent shooter, and requires very little teaching on the court - you can obviously understand why Mr. Mascari played a ton of minutes. Yet it still fails to appropriately sum up how unique and uniquely weird his on-court impact was.

Since 2002-03, the first year with individual games played data at Stathead, there have been 1,506 registered players with at least 35 minutes per game and 30+ games played. Mascari ranks 1,492nd in Usage%, T-1,503rd in offensive rebounds (five, total), T-1491st in blocks (one), and 1,492nd in PER (10.4). None of the players below him, save for 2023-24 Tyler Patterson of Montana State (the 2005-2024 Innings Eater record-holder for all of 12 months), made the NCAA Tournament, much less served as a key member of a Tournament team that easily handled a 6 seed and pushed a 3 seed for 30+ minutes.

Perhaps that is the beauty and the strangeness of the Innings Eater. What they are doing may, at times, seem like a whole lot of nothing. I wouldn't doubt that Mitch Mascari is very much fit and will have a nice career in local 10K/half-marathon happenings if he chooses to go that path. Sometimes, you gotta eat innings. A whole lot of them.

Drake's team ended up not being very deep last year, with the rotation being whittled to seven players by Tournament time and a rare eighth in Kael Combs. As a guard, Mascari was actually asked to do a lot of things that make up winning: make shots, don't foul, don't turn the ball over, stay in front of your man, and do your job. Given his status as a fifth-year leader that hit over 40% of his 3s, had the highest DRAPM of any Drake player, and the ability to suck up a ton of minutes - 1,304 versus D1 competition overall out of a possible 6,725 - who can say he didn't succeed wildly, much like the Innings Eaters of our youth? After all, outside of Stirtz, Mascari was the best player on the roster at spotting the litany of off-ball cuts the McCollum offense produces.

I have had odd favorite players before in college basketball - see my years-long fandom of one Ja'Vier Francis - but Mascari's ability to break a traditional view of statistical impact was oddly refreshing as a neutral observer. It reminds me of a younger, more innocent time, one where I had no idea what a WARP was or if it was good or bad to have a high DBPM. One where you just saw a guy play and were sort of mesmerized that he never, ever left the court, or the field, or the arena.

Anyway, it seems the finance world will have to wait a little while longer.

Maybe there is some hidden value in doing nothing, huh?