How long can you avoid the Regression Monster?

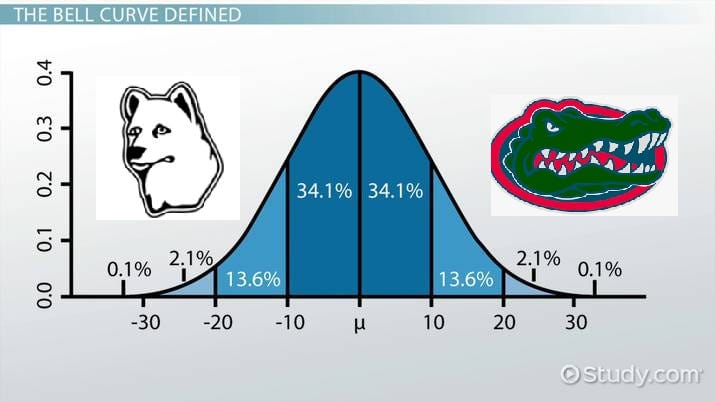

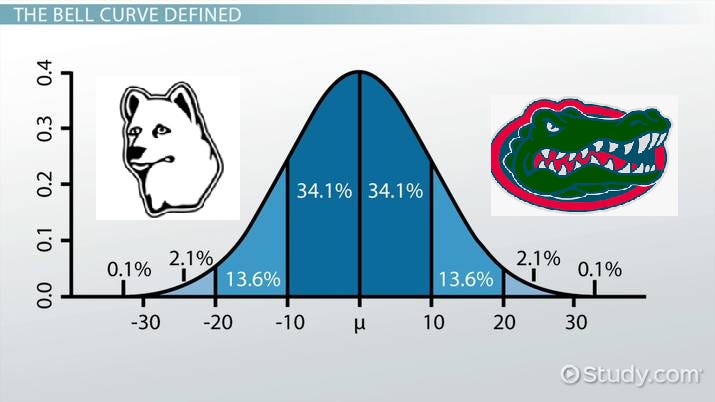

I have thought about this a lot lately because of two very similar basketball teams experiencing extremely different outcomes to the 2024-25 season: the Florida Gators and the UConn Huskies.

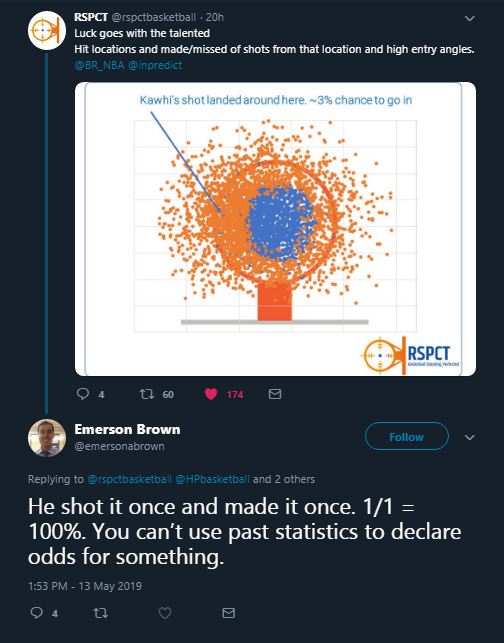

There is a post I think about a lot. It is from the before times, aka pre-COVID, after Kawhi Leonard made The Shot. The original post is long gone, and I had to dig through a couple different Twitter searches to find it among previous posts of my own. But it is this.

It feels like a primeval version of the average person’s revulsion to analytics in the first place. The shot went in, so it must have been a good attempt that was never going to miss. This shot.

Now, the original poster (RSPCT Basketball) has posted once in the last four years, and Emerson Brown is no longer active at that account handle. Things change. I do think we’ve made major progress in how analytics are discussed, handled, and dealt with basically everywhere. At the time that shot occurred, Nate Oats had just left Buffalo for Alabama and no one outside of Division 2 fans had heard of Josh Schertz or Ben McCollum.

Still, the post makes me think so often about probability. Partially because when I went to the Henry Ford Museum with my wife in the offseason I saw Mathematica for the first time, but moreso our inability to take probability on a shot-by-shot basis. Think of it this way: when Reyne Smith, national leader in made threes among high-major teams (68 made shots, 38.6% 3PT), attempts this shot:

Your guess when it’s released is “oh, that’s probably going in.” Smith is a 39.1% 3PT% shooter on catch-and-shoots this year and 47.4% on open ones, which this one is. This shot does not go in.

Here is the exact same action against a superior defense in Virginia. It is reasonably, although not perfectly, guarded. It produces the exact same shot in the exact some spot of the court with the exact same amount of seconds left on the shot clock. This shot goes in.

By either metric you choose - 39.1% or 47.4% - a miss is more likely to happen than a make when Smith attempts this shot. It does not feel that way to us in real time, because our brains take the binary as presented by Mr. Brown: if it is a good shot by a good shooter, it deserves to go in. The ball never lies, except it does every single game with pretty high frequency.

Even by the second number of 47.4%, that’s basically ten flips of the coin. It is most likely that this coin will come up with a YES (in our scenario) five times out of ten, but it could also be seven out of ten or three out of ten. It could also mean Smith makes this shot four times in a row, but proceeds to miss five of the next six despite doing nothing functionally different. He still makes 50% of his shots, but we think of him as being in a mini-slump because he’s 1 for his last 6 from deep.

I have thought about this a lot lately because of two very similar basketball teams experiencing extremely different outcomes to the 2024-25 season: the Florida Gators and the UConn Huskies. Both teams have top-10 offenses, are excellent on the boards, don’t generate (or give away) many turnovers, are top-20 in opponent 2PT%, and have low defensive Assist Rates and Three-Point Attempt Rates. Both are led by analytically-friendly coaches that play modern basketball.

And yet: one is 15th in defensive efficiency. The other is 128th. In a make-or-miss sport, one team is running tremendously hot on the probability front. The other is experiencing the worst shooting luck of any decent basketball team this year. Why? How? Well, here’s an attempt to answer and to show what ends up happening to teams like Florida and UConn that are good at basketball but experience unusually hot or cold runs of play defensively.

BEHIND THE WALL ($): The Regression Monster lurks

Stats By Will is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

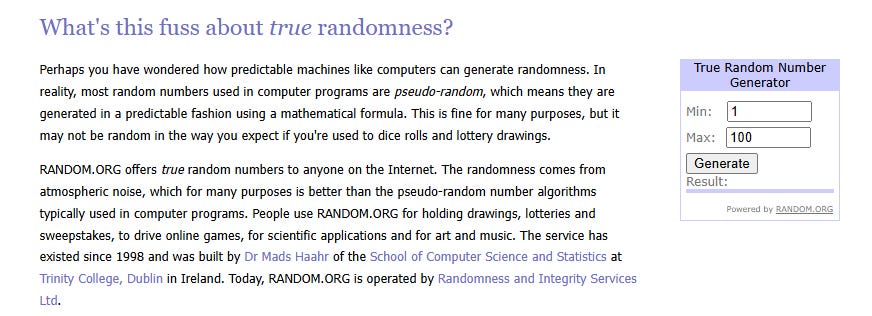

Let’s play a little game. Go to RANDOM.ORG. The first thing you’ll see is this:

Click that Generate button ten times. My results were 81, 12, 69, 23, 73, 12, 95, 24, 65, 5. Let’s say that my true 3PT% is 35%. Anything over 35 is a miss. Despite being a real 35% three-point shooter, I went 5-for-10 from the field in this sample, alternating misses with makes. Run it again ten more times, as I did, and you may go 3-for-10, missing four attempts in a row to begin. Run it 100 more times, and the likelihood we get closer to my true 35% shooting percentage grows exponentially.

This is just one example, but the smaller the sample size is, the deeper the randomness may feel. Every single shot is its own sample, but a season’s worth of shots is a much more worthy sample. A game’s worth of shots is barely a sample at all. Remember 2017-18 Villanova, the greatest college basketball offense in modern history? They started their season shooting 7-32 (21.9%) from three. Their true 3PT%, per 40 games of data, was 40.1%. But I am reasonably certain at least one message board poster, attendee, or Twitter person said Villanova took too many threes in that first game.

As of now, both Florida (18 games) and UConn (19) have fairly sizable sample sizes, but they’re not gigantic. Per research from Kostya Medvedovsky, after approximately 242 individual three-point attempts, your numbers are more real than they are noise. Those are player stats, though; for a team, per Krishna Narsu, it took approximately 33 games in the NBA for opponent 3PT% to stabilize and 26 games for a team’s own 3PT%.

This is a lot of discussion to say the following thing: Florida has been lucky and UConn has not. Per objective shooting data from Synergy, Florida would be expected to have allowed a 33.4% hit rate on threes. UConn: 33.7%. The actual numbers are 27.7% (-5.7%) and 37.4% (+3.7%). On all jumpers, it would be an expected 0.93 points per shot allowed by Florida; for UConn, 0.89. The actual numbers: 0.76 for Florida (-0.17 PPS), 0.99 for UConn (+0.1).

So: I began digging. The Gators this year have allowed 137 unguarded catch-and-shoot jumpers this year, per Synergy. UConn has given up just 79 despite playing an additional game. Yet Florida’s open threes allowed have gone in at just a 32.1% rate, about 4% lower than expected. This is not because they’re giving up shots to the right players, a la UC Irvine; they’re getting lucky. Chaz Lanier, he of 69 made threes this year and a 43% hit rate, got three wide open attempts against the Gators. He missed all of them.

Meanwhile, UConn’s open threes allowed have gone in at a 40.5% hit rate. 64% of all catch-and-shoot attempts by the Huskies have been guarded, per Synergy, to 57% for Florida. UConn has faced a slightly tougher SOS and opponent 3PT%, per Hoop-Explorer and Synergy, so we would expect them to perhaps have a similar 3PT%. They do not. Here is Curtis Williams Jr., career 31% 3PT% shooter with a 91 ORtg, nailing the open shot UConn gave up.

Now, this is not me saying UConn’s open threes allowed are all to bad shooters. Go through Synergy’s playlist and you’ll find wide open looks by the likes of Steven Ashworth, Bensley Joseph, and Jeremy Roach. But the catch-and-shoots are just one aspect.

In general, dribble jumpers are the least efficient style of jumper one can take. The average shot quality of these is nearly 10% worse than the average catch-and-shoot attempt. As such, it’s a great sign for UConn’s defense that they force more dribble jumpers than any other defense in America. It is probably less of a good thing that their opponents are shooting 37.5% from deep on dribble jumpers, the 10th-worst hit rate for anyone in America. Last night, I got a DM from No Escalators demanding me to put this one in here as the latest example of Dumb Stuff.

Florida is getting the complete other side of the equation here. Per Synergy, opponents would be expected to score about 0.81 points per shot on the style of dribble jumpers the Gators and Todd Golden are giving up. They’re instead at 0.64, the 11th-best rate allowed in America. This isn’t because Florida is forcing a ton of these attempts; they sit 123rd in dribble jumper attempt rate in the nation. Opponents are shooting 28% on 2PT jumpers (23rd-best) and 23% on threes (32nd). Together, Florida rates seventh-best in opponent FG% below expectation.

But: are they actually doing anything to encourage these shots to be so bad? Florida actually allows one of the highest Synergy Shot Quality numbers on dribble jumpers because they’re allowing the 23rd-highest three-point attempt rate on them. I wondered if these could be due to Florida perhaps harassing opponents on the perimeter (not really; 96th-highest Steal%), forcing really long possessions (also not really; 246th-longest avg. possession length on D), or forcing more long range threes (national average) than usual. All of these were a no; they’re just getting a bit lucky in the ways UConn isn’t.

None of this is a crime. Florida has legitimately fantastic rim protection and their defensive system is built around funneling opposition to the rim to get stuffed, so you could rationalize these results as opponents being frazzled into bad shots. But UConn also has fantastic rim protection, sitting in the 95th-percentile nationally, and utilizes a very similar defensive system. So why are two teams experiencing such diverse outcomes?

It helps to remember that this happens every year to someone. In 2023-24, North Carolina gave up a 28.4% hit rate from three over their first 19 games. They were 16-3, had a top-15 defense, and around this time of the year, the Athletic wrote a piece about UNC’s championship-level defense. The rest of the way, UNC opponents shot 36.2% from deep and UNC gave up 89 in their Sweet Sixteen loss. Did people see this as variance? No. They said UNC needed to get back on track defensively, despite allowing THE EXACT SAME 2PT% over the first 19 games and the last 18.

Meanwhile, in 2021-22, Arkansas gave up a 34.7% hit rate from three over their first 19. Eric Musselman himself said Arkansas wasn’t “defending the ball from three” after giving up 89 points to Hofstra. They were more likely to miss the Tournament entirely than to be their standard 3-5 seed. The rest of the way, Arkansas’s opponents shot 29.8% from deep and they made the Elite Eight as a 4 seed. Guess which unit got all of the credit.

Now, did either of these teams do a single thing differently the rest of the way after their hot or cold starts? No. UNC’s Guarded/Unguarded split dropped by 2%, but they actually forced more jumpers off the dribble. Didn’t matter; opponents shot 4-6% better on each. Meanwhile, Arkansas’s Guarded/Unguarded split had no difference. They forced about 1.5 more dribble jumpers a game, mostly by running shooters to the 17-20 foot zone of the court, but there was nothing that different objectively speaking. Yet opponents shot 10% worse on guarded threes and 5.5% worse on dribble jumpers overall.

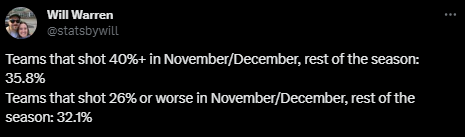

In the past, I mentioned this note on November/December hot/cold shooting versus the rest of the way:

But this was on offense, not defense. Still a big deal! Just not a perfect 1:1 comp. So: post-COVID, high-major teams that allowed a 28% or lower hit rate from three over the first two months of the year allowed a 32.3% 3PT% the rest of the way. Teams that allowed a 38% or higher hit rate, as UConn did before last night: 34.9% 3PT% the rest of the season. Basically, Florida is probably a little better at defending threes, in theory, but we don’t really know. We certainly don’t know that they’re 10% better at it.

This is a 2.6% difference between two teams currently split by 10%, and it doesn’t even take into account Florida allowing a 26.2% hit rate on two-point jumpers to UConn’s 33.3%. Still, we can take two things to heart here: Florida’s probably not got magic three-point beans after allowing a 32.1% hit rate over Todd Golden’s first two years, and UConn has not suddenly become horrid at perimeter defense after Dan Hurley allowed a 30.5% 3PT% the last two years. Patience pays off sometimes.