With 4:52 on the game clock left in their Round of 64 battle with Missouri this March, Drake led the game, 52-50. They'd been holding on for dear life for some time, but the ball made it to their best catch-and-shoot option in Mitch Mascari on the wing. With a second left on the shot clock, after traveling, he let one fly. It didn't touch anything but air, and it's listed as a shot clock violation.

This was one of Drake's 206 non-steal turnovers in 2024-25. Per CBB Analytics, it was one of the 129 dead ball turnovers in their classification system. Excluding a couple of games against non-D1 opposition, Drake racked up a turnover rate offensively in the 31st-percentile nationally, which would've told you they had a turnover problem. And yet: the Bulldogs were actually in the 65th-percentile nationally in terms of preventing live-ball turnovers on offense.

This occurrence - a possession dwindling down to the very last second - was one of the most normal occurrences in any given Drake game last year. An impressive 41% of Drake's first-shot attempts last year came in the final 10 seconds of the shot clock, the highest rate in the sport by some measure. At Synergy, Drake averaged 11.8 possessions a game where they touched the final four seconds of the shot clock. The gap from them to second-place North Texas was the same as the gap from UNT to 42nd overall.

Obviously, it's not like we haven't had extremely slow offenses before. In their peak slow age of 2018-19, Virginia took 21 seconds per possession on average and managed the second-best offense in the sport out of it. Yet Virginia had a super-low TO% (14.7%, 12th-best) and the third-lowest non-steal TO%. Drake, meanwhile, finished 354th of 364 in non-steal TO%. Despite this, they were the first team since 2016-17 Baylor to finish in the bottom 20 of the stat nationally yet both have a top-100 offense and win an NCAA Tournament game.

These were all things I didn't notice at the time. If I had, I probably would've written about it somewhere, and Lord knows I've had more than a few opportunities in the 2025 calendar year to word vomit about Drake and/or Ben McCollum. But it wasn't until Jon Fendler pointed out the unusual steal to non-steal gap here - more dead-ball turnovers than live ones, and the minor math edges one can find in the sport - that it finally clicked.

Earlier in the year in November, Drake would announce their arrival to the season by winning the Charleston Classic, beating all of Miami, Florida Atlantic, and Vanderbilt by double digits. If you just saw the points scored in these games by Drake - 80, 75, 81 - you'd have no real idea that each game's pace was heavily controlled by the Bulldogs. In fact, Drake took 42 of their 162 field goal attempts, or 26% of all shots, in the final four seconds of the shot clock, per Synergy.

Yet again, though, it wasn't a beautiful late-clock make by Bennett Stirtz or some sort of bailout foul that stuck with me. It was a possession with a missed shot and a turnover midway through the second half of the Florida Atlantic game that seemed to sum up the spirit of Drake. With 9:03 to go, Tre Carroll sinks a free throw to get FAU down to a 53-48 deficit. Tavion Banks misses an open pick-and-pop jumper, but Nate Ferguson gets the offensive rebound.

20 seconds later, with the clock withering, Tavion Banks turns the ball over out of bounds with just 0.2 seconds left to shoot. Even in the most positive outcome here - the ball deflecting off of an FAU player - it's still very likely a shot clock violation, or worse, a live-ball turnover. But this dead-ball turnover did matter against FAU. Why? The Owls scored 16 more points per 100 in transition than in half-court offense, and in a two-possession game, even functionally punting the ball away was better than getting intercepted.

On FAU's next possession, they took a shot, missed, and didn't get the rebound back. 53-48 was the closest the score would be the rest of the way.

In general, across sports, we're taught that turnovers are bad. Nothing's more demoralizing than giving up a pick-six, getting caught stealing, a giveaway that leads to a breakaway in hockey, or, honestly, the worst kind of turnover:

But in basketball, I'm not sure I've ever seen a graphic in-game that differentiates between steals and non-steals. Frankly, it's hard enough to get eFG% or any sort of percentages mentioned beyond basic field goal percentage. Broadcasts go with total numbers: assists, turnovers, rebounds (though they've begun to separate out offensive ones), free throws, etc. The average person viewing the game is only interested in the score, for better or for worse. They don't particularly care how it got there unless it's blindingly obvious.

The reason I care about the difference between live-ball and dead-ball turnovers is that one generates significantly greater points for your opponent than the other. On average in 2024-25, live-ball turnovers resulted in 1.17 points per possession; dead-ball turnovers, meanwhile, sat at 1.03. When taken purely as "how did you shoot from these," live-ball turnovers generated possessions with an 8% higher 2PT% and, surprisingly, 2% higher 3PT%.

The latter part makes sense, because live-ball turnovers lead to shorter possessions and greater opportunity to play in transition. In the first 10 seconds of the shot clock, per CBB Analytics, almost 55% of all shots are taken at the rim or in the paint. In the final 10 seconds, that falls to 46%. This matters for far more reasons than you'd expect:

- The 2PT% and 3PT% produced in the final 10 seconds of the shot clock falls to 43% and 31%, respectively.

- The average shot goes from roughly 10 feet away at the start of the shot clock to almost 14 feet away by the end.

- Offensive rebounding rates drop dramatically on midrange twos (26%), above-the-break threes (27%), and corner threes (30%) versus shots at the rim (36%) or in the paint (31%).

- In fact, the first shot attempted in half-court offensive possessions period is a bad one: 47% 2PT/33% 3PT versus 65% 2PT/38% 3PT in transition, per CBB Analytics.

Now, the last example feels extreme, and as noted earlier I'd wager the numbers aren't quite as severe a split. Still, there's an obvious advantage to limiting transition play as much as you can. Houston has made a program out of this, as did Virginia, but neither has intentionally sacrificed possessions the way Drake seemed to this year. Against the fastest team by average pace on their schedule (Indiana State), Drake put up an astonishing 19 dead-ball turnovers across two games.

You can count on me to never leave a stone unturned in the name of great journalism, particularly in these times, so of course I watched all 19. They were classified as:

- 3 dribbles out-of-bounds

- 4 lost balls

- 2 travels

- 5 bad passes

- 3 charges

- 2 shot clock violations

It's a heavy mix, and certainly, shot clock violations aren't as huge a part of it as one would gather. But: that's 19 dead-ball turnovers, and 19 missed transition opportunities for Indiana State. Across the two matchups, ISU scored 0.79 PPP (15 points) off of these 19 possessions. On the 14 live-ball turnovers, however, ISU dropped 1.14 PPP (16 points), most of which came in the first 10 seconds of the shot clock. Sometimes, simply eating a possession helps in the long run.

That's just one opponent, of course. We might as well look through the entire season. Again: in the name of leaving no stone unturned, I did so. Drake ended this past season with 38 shot clock violations in their 33 Division I games, or about 1.15 per night. Obviously, that sounds wildly high for anyone above the high school level. For comparison's sake, Saint Mary's, a fellow compatriot at the low end of the pace ranks, had 16 the entire season and used five of them up in a pair of games against Gonzaga.

McCollum's offense playing at a snail's pace is nothing new. At Northwest Missouri State, his teams ranked dead last in offensive pace in 2023-24 (20.6 seconds per possession), third from the bottom in 2022-23 (19.6 seconds), and fourth from the bottom in their final championship run in 2021-22 (18.8 seconds). While Tony Bennett is more well known for total pace control, CBB Analytics has these NWMO teams ranking 4th, 8th, and 25th in terms of possession share in an average game. Last year's Drake team, made up of mostly Northwest Missouri transfers, ranked third behind Tarleton State and Coastal Carolina.

In other sports, time of possession being a critical factor for coaches isn't that new. We've heard about the time of possession battle in football for years (which correlates with winning, but not with actual causation), and possession percentage is perhaps the only stat other than goals or shots taken that gets shown on soccer broadcasts with any regularity. (That one does matter, but mostly as a figure of showing one team as being way more talented than another.) I've never heard it mentioned before in basketball, so welcome to a clock management lesson.

In the Round of 64 game against Missouri, Drake had the ball for 21.8 minutes of the game, while Missouri owned it for 15.7. (The other 2.5 are accounted for at CBB Analytics as the ball being in the air on a rebound, held balls, and other stuff.) That's a 58% share in Drake's favor. Now, this didn't manage to even crack Drake's top five in possession share last year, coming in at 8th-highest, but it did come in as Missouri's second-lowest of the season.

For most teams, time of possession is fairly meaningless. For Drake, it held serious importance. Drake only held a 51% or lower share of possession four times in all of 2024-25; they went 2-2 in those games, and one of the wins was in overtime against Kansas State. When they were allowed to sit on the ball for 30 seconds at a time, as they were here, it seemed to take the air out of the opponent, too.

This type of philosophy - openly eating the clock away and being willing to cede 20+ seconds before getting serious - is not something you see in college basketball unless you're at a serious offensive disadvantage or you're trying to run out the clock with a lead late in a game. Drake did neither. 17 of their 38 shot clock violations occurred in the first halves of games, including this one to open their biggest win of the regular season against Vanderbilt.

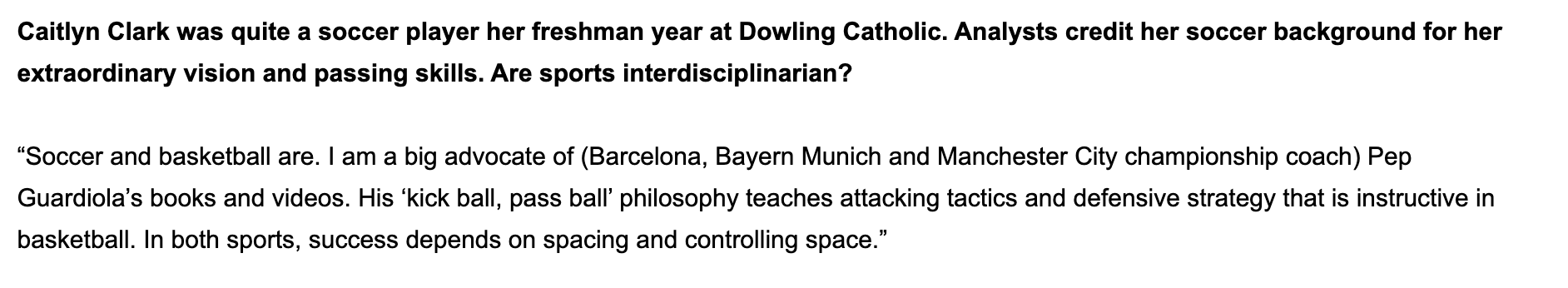

Outside of attending one Iowa women's soccer match, I would have had no idea that McCollum was into soccer whatsoever. He makes no public indications about it, and when I've interviewed him in the past he's never mentioned it. Then, I found an interview from summer 2024, three months before Drake's season would begin. Everything clicked.

Pep Guardiola has managed some of the greatest teams in European history over the last 17 years. As mentioned in that clipping, Barcelona (four years), Bayern Munich (three), and Manchester City (since 2016) have all won a lot, with Guardiola being responsible for some of their best runs. But the 'kick ball, pass ball' philosophy McCollum mentions is what we're here for.

Over the last 17 years, no manager has controlled possession or space better than Guardiola's teams. It's made easier by the fact all of Barcelona, Bayern, and Man City have gigantic bankrolls that can afford the talents necessary to run such a system, but all one has to do is look at the share of possession these teams generated under Guardiola in their respective leagues. Guardiola's Bayern teams set back-to-back club records in goal differential. In the season he didn't do such, his team controlled 70.4% of possession. Next-best in the Bundesliga, Borussia Dortmund: 55.3%.

In Guardiola's second season at Man City, the club set a Premier League record with 71% of possession (next-best: 61%) and was seen as one of the greatest English sides in history. This video from the outstanding Football Made Simple does a better job than I can of summing up just how Guardiola's tactics control time, space, and game flow better than anyone else in modern soccer history:

Reading that quote from McCollum, things finally made sense. Watch this sequence, a successful one, from the Missouri game. On the previous possession, Jacob Crews commits a live-ball turnover at the hands of Mitch Mascari with 11:50 left on the clock in the first half. It's 45 seconds until Missouri sees the ball again.

This is the other kind of dead-ball situation. 259 times last year, Drake ran the shot clock past 30 seconds thanks to an offensive rebound, the highest rate in the sport by a mile. Drake's offensive rebounding in general allowed it to control the game against Missouri (33% to 27% in OREB%) and against most opponents. No team gave up fewer defensive rebounds off of field goal attempts as a percentage than Drake, as opponents generated just 25.6% of all possessions from these.

That sort of non-stop pressure wore down opponents consistently over the course of 35 games. Drake got back 36% of its missed threes, 42% of its missed midrange jumpers, and an astonishing 46% of its missed layups, per CBB Analytics. All of those numbers ranked in the 93rd-percentile or higher nationally, which is pretty nuts for a team without a player taller than 6'8" in its rotation and whose starting PF was 6'6", 220.

What will shock you here is that this is entirely different from the teams McCollum won titles with. In 2021-22, Northwest Missouri ranked in the 52nd-percentile nationally in getting missed field goal attempts back, instead choosing to shut teams down in transition the more standard way (forfeiting second chances). Even in his final year at NWMO, the OREB% rate was in the 67th-percentile. Opponents still rarely started possessions with defensive rebounds, but it was more because Northwest simply made the first shot more often.

This sort of adaptiveness intrigues me. In the Guardiola video above, you see how a guy that's been boxed into a category of possession monster who plays 'boring' football has changed his tactics significantly from season to season. If McCollum offers the same adaptability, his strengths could carry over to higher levels, even if he's clearly not at the same talent and budget advantage his footballing hero has on a yearly basis.

Does this really matter? Maybe, maybe not. But I think McCollum has found a new Moneyball 'hack' of sorts to beat the system. In that Missouri game, which unveiled Drake and McCollum to the world more than any D2 title or glowing ESPN article could have, Drake put together 38 possessions lasting 20 seconds or longer, including 10 that went 30+. Missouri, meanwhile, had 15. Drake scored 42 on their 38 long possessions. Mizzou: 12 on 15.

It's a formula ages-old now, but shortening the game to this extreme is something many upset-minded coaches have only dreamed of. McCollum went out and did it after being the favorite doing it his previous 10 years. Now, the question looms: can he do it again?

Ben McCollum will enter his first year at Iowa with four players that were either at Division II, JUCO, or Wyoming 18 months ago. That's one storyline. The other is that, for the first time in his entire career, McCollum is going to have serious high-major talent on his team. Brendan Hausen, a career 39% deep shooter on high volume and a former top-75 recruit, transfers in from Kansas State. Alvaro Folgueiras, the Horizon League Player of the Year, passed up Kentucky, Providence, and Villanova to play for McCollum. Cooper Koch, a former top-100 recruit in 2024, decided to stay at Iowa instead of joining almost the entire roster in the portal.

Combined with Stirtz and the other Drake transfers, McCollum has likely never had this level of pure athleticism at his hands before. The speed of the game itself will be much different in the Big Ten, but then again, most of us thought the speed of the game would be different from the MIAA to the Missouri Valley. It wasn't, and McCollum ran through the league in one year without breaking much of a sweat.

To do the same again would be a gargantuan achievement, but it's unlikely for a variety of reasons. In terms of recruiting talent on the roster, Iowa is in contention with fellow new-coach, portal-heavy Indiana in the bottom three of the league. The Big Ten is not the speediest league in world history, but since the move to the 30-second shot clock, only two of its teams have gone below 63 possessions a game, none below 62. McCollum hasn't even touched 61 a game since 2020-21.

This is why, in our recent League Pass podcast about teams Jim Root and I want to watch, that I selected Iowa out of the Big Ten as an at-large spot. This is the most interesting experiment going this year in college basketball for me. How much can McCollum manipulate the game and shot clocks in his favor? How many empty possessions is he willing to sacrifice to ensure an Illinois or a Michigan doesn't bust out in transition? Can his teams control the offensive boards in the same way with more talent, but less time to gel to his system?

Above all else, I want to see the math of it all once more. It's an exceptionally extreme zig where nearly everyone else is zagging, as last year's points per game was the second-highest we've seen since 1995 and as non-steal percentage reached a record low. Can Iowa do it? Will it look the same? I don't know yet, but I greatly look forward to finding out just how well McCollum can manipulate a 40-minute calculator.